ARMORER ON THE SET!

MAKING A WESTERN MOVIE

A motion picture is, in the final analysis, the presentation of an illusory world which doesn’t physically exist, but has been created to tell a story, and to do so as convincingly as possible. Firearms and their use are often part of the illusion: it’s hard to think of a film (except perhaps Mary Poppins) in which there isn’t some sort of gun present at some point in the story. A western, a science fiction fantasy, a war epic, a detective story, all of them feature some gunplay.

Many of the “guns” in actors’ hands are merely realistic dummies, but not always. If the script calls for a gun to be fired—and it almost always does—then that gun is often a real one used with blank ammunition. To prevent accidents and to avoid damage to valuable equipment—and even more valuable actors!—the standard “best practice” is to have an expert on the set who’s trained in firearms safety and who can coach the actors in how to do their job realistically and safely. He’s the on-set armorer, and he’s a vital part of the crew. He is also the only person on the set authorized to load and unload the guns; when a scene has been finished he collects them from the actors’ hands, and hands them out only when a scene is to be shot. By putting the responsibility on one experienced person, safety is enhanced because often the actors know little to nothing about proper procedure and have to be supervised as much as the script will allow.

Thanks to being a certified instructor, an advanced gun collector, and a contributing writer for shooting and hunting publications, I recently was asked to be the armorer for a small film a friend's son was making as a project for his college major. As it happens I also have some experience behind a camera as a motion picture photographer in my military service years ago. It was a most interesting and enjoyable experience to get back to movie making and employ my expertise: I’m pleased to have been a part of the crew for a production that will be shown at several film festivals and (we hope) is likely to win some awards in the process.

The armorer’s principal role, without question, is to ensure safety on the set. He has the authority to call “CUT!” if the actors do anything at all that might be unsafe. Before the filming began I supervised a shooting session to establish safety zones and distances for use with the blank cartridges that were employed. Big-budget films today “dub” in flashes and recorded gunshots, with the actors merely going through the motions of shooting; but that’s an expensive and laborious process, so we used black powder blanks made for the Cowboy Action and re-enactment groups. Black powder makes visible smoke and flame and the cost was well within the limited budget.

We needed to know how close the actors could be to each other when shooting, for obvious reasons. There have been some terrible injuries caused by misuse of blanks on movie sets, because they aren’t as “harmless” as some people might think. To test the safety margin we set up sheets of newspaper and fired at them; as they were unmarked at 4 meters’ distance we established that as our safety zone.

Another important role was to make sure that the guns chosen for the film were “period correct,” as part of creating the illusion of reality. As one of those people who spots firearms errors in movies this part of the job was fun. Even a truly great film can be ruined for me by bone-headed mistakes in what guns are used. The marvelous combat sequences in Zulu!, for example, set at the battle of Rorke’s Drift in 1879, were marred by the use of Webley Mark VI revolvers—that weren’t in existence until 1915!

The film on which I worked was set roughly in the time period 1890-1910. It’s a semi-western; a story of tragedy, revenge, and restitution for crimes committed. It includes two brief gunfights and a scene in which two characters are out hunting. I was asked to provide guns which were not only period-correct, but which suited the action, and had a “dramatic” appearance. Again, a major concern was realism. An early-twentieth century small game hunter wouldn’t be using a Model 98 Mauser, or an autoloading rifle.

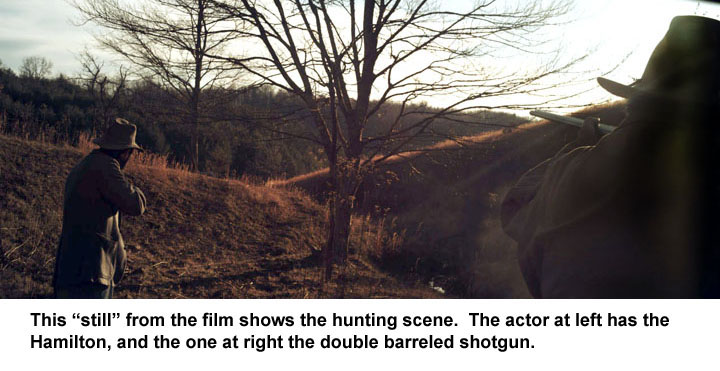

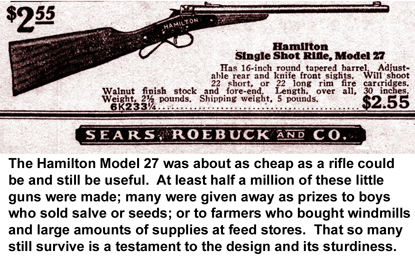

In the hunting scene one character is seen shooting at a squirrel with a single shot .22 rifle. For him I chose a Hamilton Model 27 “boy’s rifle,” a gun produced in prodigious numbers after its introduction in about 1907. The Hamilton was very inexpensive—many were given away as premiums for buying a windmill or a cartload of grain, or for selling cakes of salve—and many a squirrel and rabbit found its way to the dinner table of some rural family via the business end of one of these little guns. The hunting partner was to be equipped with a shotgun. The director was very specific about this: he wanted a double-barreled shotgun, again for reasons of dramatic impact. The shotgun also plays a vital role in the final scene of the film, in which both barrels are fired simultaneously for visual effect.

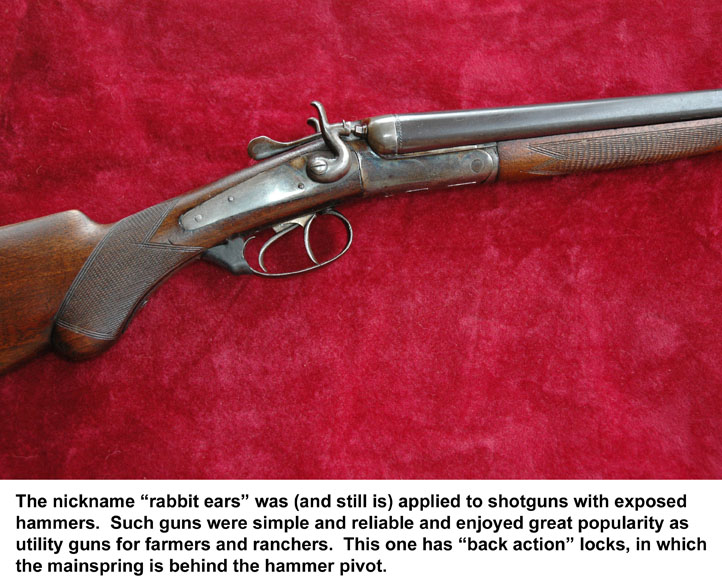

For this character I was able to provide a generic Belgian-made “rabbit ear” double, i.e., one with external hammers. The great post-Civil War westward expansion of the United States created a huge demand for shotguns, and the Belgian arms industry shipped hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of inexpensive doubles, typically with back-action locks and external hammers. They were sold in immense numbers in local hardware and feed stores, or through the big mail-order houses. Every home in rural areas—and most in urban ones—contained some sort of shotgun. People moving westward, whether by wagon or railroad (or for that matter, by automobile, and well into the 20th Century) typically brought a shotgun along for foraging and personal protection. If there was a farmstead in the 1890’s that lacked a shotgun sitting behind a kitchen door, it was a rare one, indeed.

Two period-correct handguns and a rifle were needed. We borrowed an Italian-made copy of the Winchester 1866 “Yellow Boy,” whose brass receiver has a great deal of visual appeal, from a local Cowboy Action shooter. One of the handguns was the iconic Colt Single Action Army, introduced in 1873 and familiar to all movie-goers from countless westerns. Our version was actually a well-used reproduction, chambered for .45 Long Colt.

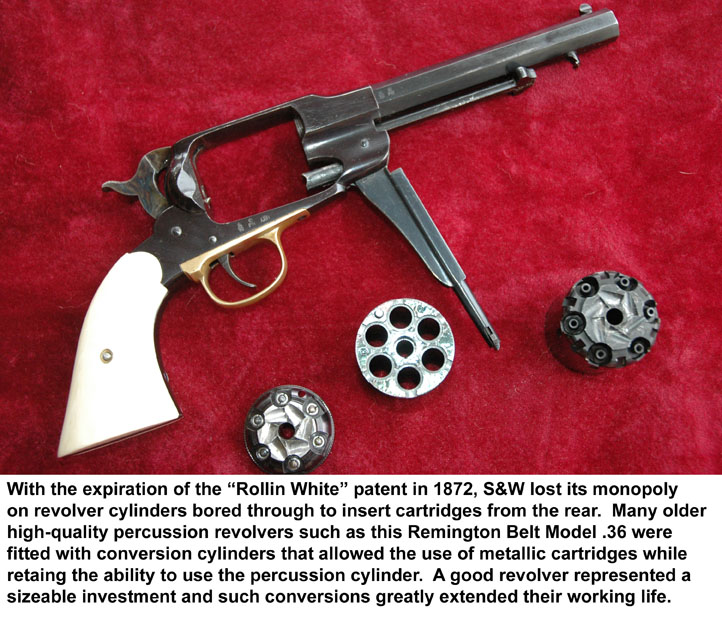

The second handgun presented some challenges. It had to be visually appealing, and a Remington Model 1863 Belt Model revolver in .36 caliber is certainly that. But percussion ignition isn’t all that reliable, and reloading it with loose powder and a wad is a tedious process. To minimize the necessity for re-takes and the time spent on shooting the gunfight scenes, we needed something that looked good but could be relied on to go BANG! every time it was supposed to.

Fortunately, there was a period-correct solution. With the introduction and widespread use of metallic cartridges after the Civil War, many existing high-quality percussion revolvers were retro-fitted with conversion cylinders that allowed them to be used with self-contained ammunition. These came in various forms, but the common ones for the Remington guns consisted of a cylinder with a removable back plate. Dropping the cylinder allowed cartridges to be inserted into the chambers; the back plate was replaced and the cylinder put back into the frame. Much faster than the usual loading procedure and providing far more reliable ignition. Conversion cylinders for current-production replica black powder revolvers are sold, and we fitted the 1863 with one of those.

As mentioned above, the actors are often (perhaps usually) pretty ignorant when it comes to firearms: not just in safe handling, but also in how they’re used by people familiar with guns. The actors with whom I worked needed coaching in how to hold a gun when firing, how to cock it, and how to look like they really were comfortable with tools that would have been in daily use by their characters. So another part of the armorer’s job is to provide coaching and drills in this aspect, including how to draw smoothly from a holster, how to present the piece, and how to fire it in a convincing manner. Anyone who’s been shocked by the irresponsible and outrageous gunplay seen in some films will understand that this is really needed not only for safety but for realistic interpretation of a role. Fortunately, “my” actors were a group of enthusiastic young professionals who took instruction well, learned quickly, and brought off their characters’ actions beautifully. Nevertheless, following protocol, I disarmed them after each scene was finished.

I had a great deal of fun with this project, and it was also

very interesting to see how far the technical aspects of film making have

advanced in the 40+ years since I was behind a camera. Today everything is digital, and film is

fading out of use. Digital cameras

provide a film-maker and his director of photography with great versatility in

the “look” of a movie, and are far cheaper to operate than ones using

film. They also allow instant evaluation

of a take, and an immediate re-take if desired. In my day we used 16mm film that required at least 72 hours to process

before a scene could be evaluated, and cost far, far more per minute of screen

time.

I had a great deal of fun with this project, and it was also

very interesting to see how far the technical aspects of film making have

advanced in the 40+ years since I was behind a camera. Today everything is digital, and film is

fading out of use. Digital cameras

provide a film-maker and his director of photography with great versatility in

the “look” of a movie, and are far cheaper to operate than ones using

film. They also allow instant evaluation

of a take, and an immediate re-take if desired. In my day we used 16mm film that required at least 72 hours to process

before a scene could be evaluated, and cost far, far more per minute of screen

time.

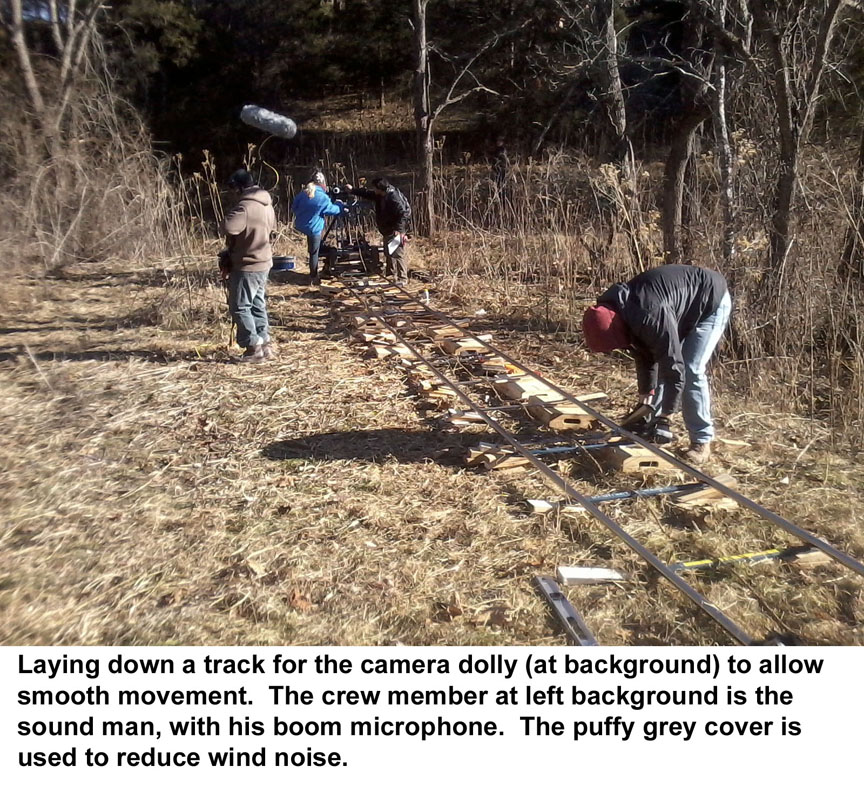

Movie making is a meticulous and elaborate procedure. A scene that lasts 30 seconds on the screen can easily take a day to shoot, even if everything goes perfectly. The cast is typically a small percentage of the numbers of people involved, far outnumbered by the grips, cinematographers, gaffers, sound technicians, make-up artists, costumers, production assistants, continuity assistants, script writers, and yes, the armorer, all of them parts of the team creating that simulacrum of reality.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |