A HUNTER'S LIFE STORY

There has been much written on the subject of hunting, mostly by people waxing lyrical about why they hunt. This essay isn’t about that: I don’t have to justify hunting any more than my dog has to justify chasing squirrels. I’m sometimes asked (by people who don’t know any better) why I want to kill “harmless animals,” and however naïve it may be it’s a valid question. One answer is “To eat them,” which is what I usually do. Another is “Because it’s in my genes,” which is equally valid, I think. I certainly don’t owe anyone an apology for being a hunter, except perhaps the animals I kill. And by the way, I do say “kill,” not “harvest.” The latter word is a euphemism that always grates on my ears as a mealy-mouthed semi-apology.

I want to describe how a city kid from a completely non-hunting background became an active hunter, some of the steps I took along the way, and how I do it now that I think I’m reasonably good at it. This isn’t a “how to hunt” piece. It’s how I hunt, not how you should hunt: and about what works for me. I suppose also that in some it’s ways a clarification for myself of what I’ve done for the past 50-odd years.

The fact is that I was a hunter long before I ever went hunting. Everyone living today, even the hardest-core vegan nutcase (whether he/she/it realizes and admits it or not), has descended from a long line of successful hunters stretching back to the Pleistocene. Had any of my direct prehistoric ancestors not been successful hunters they’d have starved to death or ended up as saber-toothed tiger shit and I wouldn’t be here at all. To paraphrase René Descartes, “They hunted, therefore I am.”

The fact is that I was a hunter long before I ever went hunting. Everyone living today, even the hardest-core vegan nutcase (whether he/she/it realizes and admits it or not), has descended from a long line of successful hunters stretching back to the Pleistocene. Had any of my direct prehistoric ancestors not been successful hunters they’d have starved to death or ended up as saber-toothed tiger shit and I wouldn’t be here at all. To paraphrase René Descartes, “They hunted, therefore I am.”

I was born and raised in the Bronx, a part of New York City where “wildlife” meant street pigeons and the odd backyard squirrel. Although I was fortunate enough to grow up at a time when hunting wasn’t yet actively demonized in American society, nevertheless it wasn’t in any way encouraged in the working-class neighborhood in which I lived. My late father was a physician who had zero interest in hunting or the outdoors, a man who was in many ways the Ultimate Urbanite. Nobody I knew hunted. I had no uncles nor even knew any adult men who could show me what to do.

BEGINNINGS

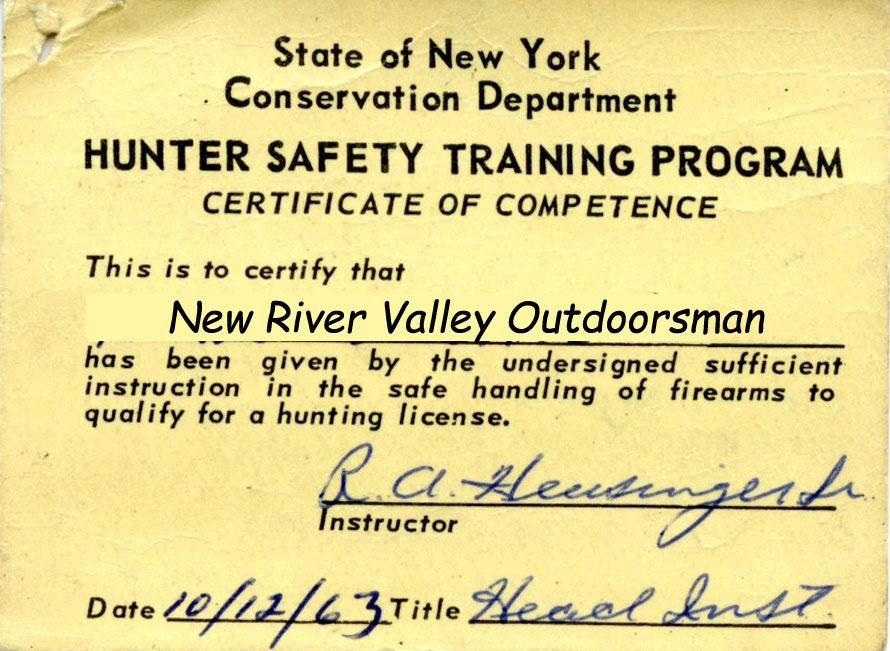

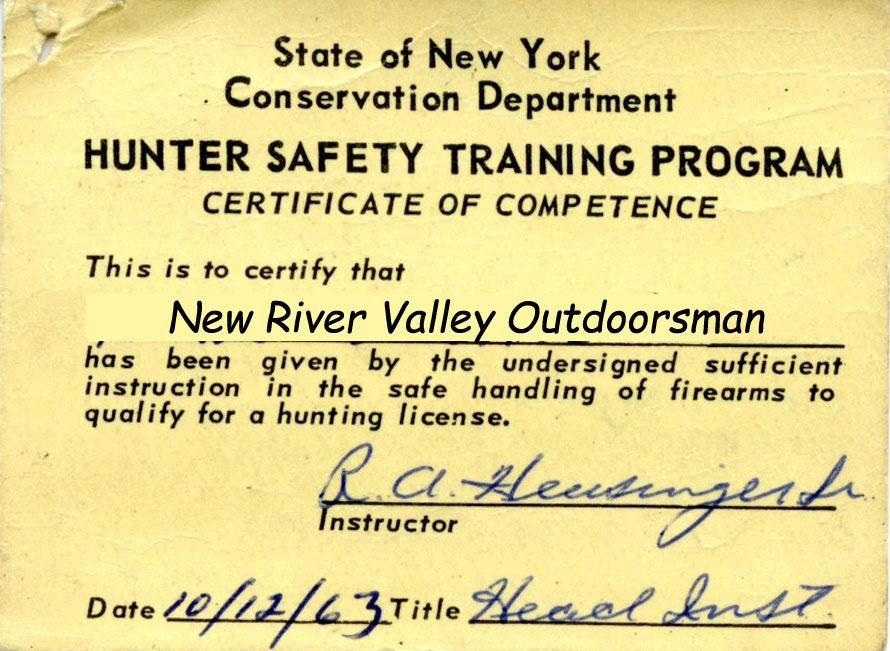

In late 1961 when my father bought a weekend house in the country I gained a substantial patch of woods in which to roam and in which I could theoretically go hunting. But lacking guidance I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to do—and in any event I couldn’t buy a license until I took the state-mandated Hunter Safety course. I did that in October of 1963 in an incredibly hot and stuffy attic over a gun shop in Yonkers. Today I’m a Hunter Education Instructor. My classes always include kids 7, 8, or 9 years old who've been hunting with their fathers from the time they could sit up, but I went into that Hunter Ed class with zero experience. I had nothing but strong interest, the firm intention to hunt and the sketchy information I was able to gather from magazines.

In late 1961 when my father bought a weekend house in the country I gained a substantial patch of woods in which to roam and in which I could theoretically go hunting. But lacking guidance I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to do—and in any event I couldn’t buy a license until I took the state-mandated Hunter Safety course. I did that in October of 1963 in an incredibly hot and stuffy attic over a gun shop in Yonkers. Today I’m a Hunter Education Instructor. My classes always include kids 7, 8, or 9 years old who've been hunting with their fathers from the time they could sit up, but I went into that Hunter Ed class with zero experience. I had nothing but strong interest, the firm intention to hunt and the sketchy information I was able to gather from magazines.

Today I teach Hunter Ed with a battery of well-done Power Point presentations, slick professionally-produced videos and hands-on demonstrations, none of which were available in that Yonkers attic. It was done on a chalkboard, with droning “lectures” and minimalist pamphlets, presided over by a couple of dedicated volunteers. My Hunter Ed students now, even the very youngest, often seem to be bored to tears by the snazzy material I get to use; but despite the lack of any sort of “flash” in the course I took, I was always excited and eager for the next topic. Among the things handed out was the NY State brochure of hunting regulations and rules about what you could and couldn’t do. I literally memorized that booklet. I read it over and over, and every year I got a new copy and memorized that. I knew it inside out and backwards and still remember parts of it.

Today I teach Hunter Ed with a battery of well-done Power Point presentations, slick professionally-produced videos and hands-on demonstrations, none of which were available in that Yonkers attic. It was done on a chalkboard, with droning “lectures” and minimalist pamphlets, presided over by a couple of dedicated volunteers. My Hunter Ed students now, even the very youngest, often seem to be bored to tears by the snazzy material I get to use; but despite the lack of any sort of “flash” in the course I took, I was always excited and eager for the next topic. Among the things handed out was the NY State brochure of hunting regulations and rules about what you could and couldn’t do. I literally memorized that booklet. I read it over and over, and every year I got a new copy and memorized that. I knew it inside out and backwards and still remember parts of it.

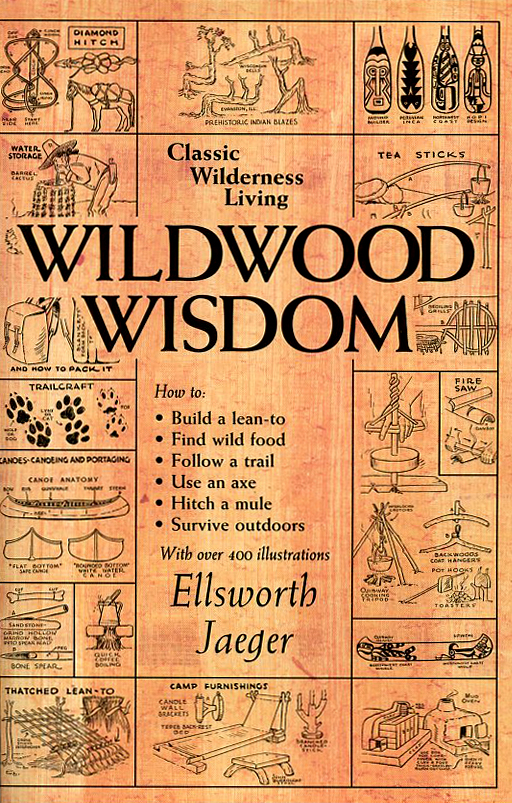

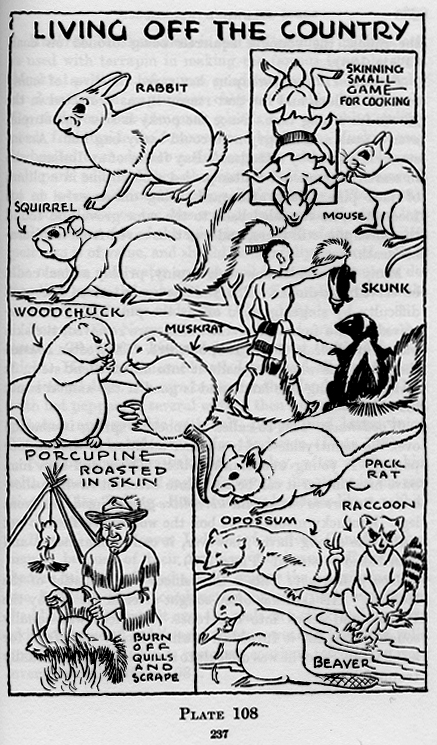

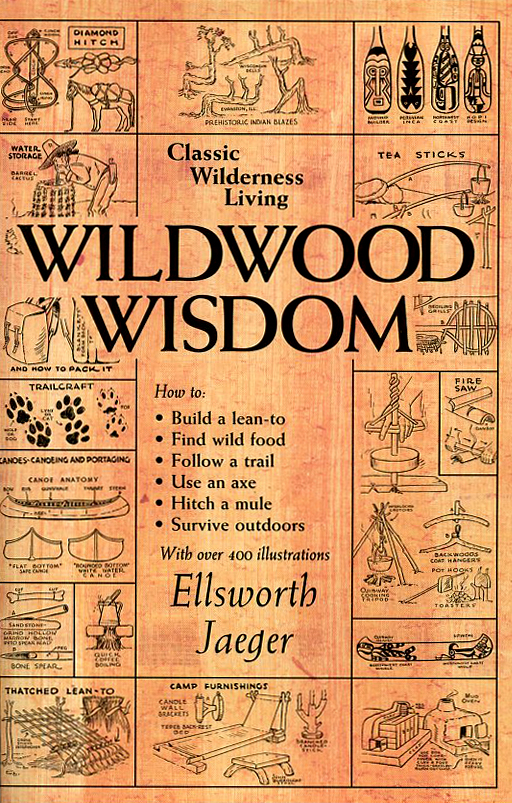

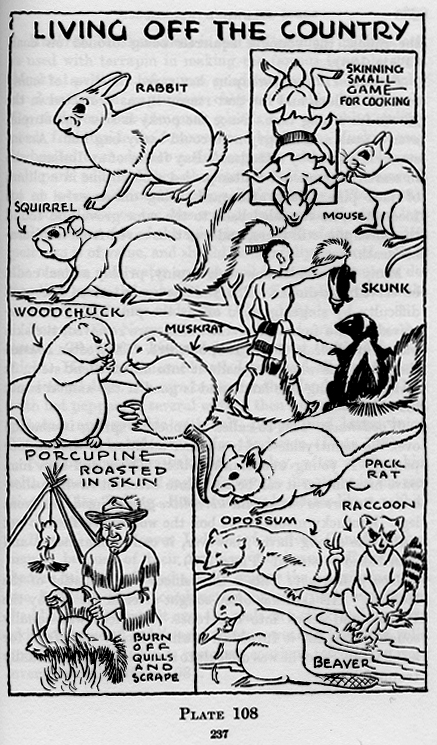

I had to learn whatever I could about hunting in the only way I could: by reading books and outdoors magazines. One big help was the fact that my school library—in the Bronx High School of Science, believe it or not—had a  copy of a wonderful book, Wildwood Wisdom by Ellsworth Jaeger. It didn’t have much in the way of actual hunting instruction but it was chock full of all kinds of information on woodcraft and skills for camping and life in the wild; and there was even a chapter on “Useful Animals and Birds.” One illustration showed how to skin small game, and how to roast a porcupine. I’ve eaten porcupine (in Africa) but never, thank goodness, have I had to skin one. I use the method illustrated in Plate 108 to skin squirrels and rabbits to this day. I devoured every word of Wildwood Wisdom; it was tremendously important in helping me firm up my plans to become a hunter. It’s still in print after more than 70 years, sold by Amazon, and well worth the price.

copy of a wonderful book, Wildwood Wisdom by Ellsworth Jaeger. It didn’t have much in the way of actual hunting instruction but it was chock full of all kinds of information on woodcraft and skills for camping and life in the wild; and there was even a chapter on “Useful Animals and Birds.” One illustration showed how to skin small game, and how to roast a porcupine. I’ve eaten porcupine (in Africa) but never, thank goodness, have I had to skin one. I use the method illustrated in Plate 108 to skin squirrels and rabbits to this day. I devoured every word of Wildwood Wisdom; it was tremendously important in helping me firm up my plans to become a hunter. It’s still in print after more than 70 years, sold by Amazon, and well worth the price.

Other more contemporary sources were readily accessible. Field & Stream magazine (and possibly Outdoor Life) was sold in the candy stores in my neighborhood, God alone knows why. Such magazines weren’t too useful to me at first because the stories assumed a certain level of knowledge that I lacked. Furthermore, while most of the stories were about deer hunting, the rest usually were about hunting grizzlies and bighorn sheep out west, it being the era of Ted Trueblood and Jack O’Connor. But the articles did put me in touch with the zeitgeist of American hunting and some of them contained useful information on technical subjects such as what gun to use for deer, the advantages of telescopic sights (by no means so universally used as they are today) and the best shot sizes for small game.

FIRST QUARRY

Not long after my father bought that country property I acquired a BB gun, a Daisy lever action. I used that gun so much I eventually wore it out, becoming proficient enough to pick off ants crawling on the driveway, and able to hit anything a BB launched from it could reach. I wish I could shoot that well today! It’s no exaggeration to say that I must have put well over 100,000 shots through it in the course of its working life.

Not long after my father bought that country property I acquired a BB gun, a Daisy lever action. I used that gun so much I eventually wore it out, becoming proficient enough to pick off ants crawling on the driveway, and able to hit anything a BB launched from it could reach. I wish I could shoot that well today! It’s no exaggeration to say that I must have put well over 100,000 shots through it in the course of its working life.

Even though I wanted to hunt deer, I had to wait until I was 16 to get a big game license. Other species could be hunted, though, not all of them entirely legally. A 13 year old boy with his first BB gun isn’t too conscientious about game regulations, and my very first kill was a sparrow I shot with that little Daisy. I was probably as surprised as he was, but he was dead and I wasn’t. I remember picking up its little body and seeing a drop of blood at the end of his beak. I felt bad about what I’d done, but then the merciless sang-froid of a teenager kicked in. “Well,” I said to myself, “if I do this some more it won’t bother me.” I tossed the body into a bush and set off on my hunting career.

WOODCHUCKS

I haven’t hunted woodchucks actively in a very long time but in 1962 I nagged my father into buying me a .22 rifle, a Remington Nylon 11 which I still have. I fitted it with a fixed 4x scope that I bought at Macy’s department store in Manhattan. That alone tells you how much society has changed: not only rifle scopes but guns were sold in Macy’s in 1962. I think my father bought that rifle just to shut me up, and perhaps also because when he’d bought the house and contents there was a shotgun in it, which I had immediately appropriated. I imagine he felt that if he didn’t buy me a .22 I’d get that shotgun out, and that had considerably more destructive potential.

I haven’t hunted woodchucks actively in a very long time but in 1962 I nagged my father into buying me a .22 rifle, a Remington Nylon 11 which I still have. I fitted it with a fixed 4x scope that I bought at Macy’s department store in Manhattan. That alone tells you how much society has changed: not only rifle scopes but guns were sold in Macy’s in 1962. I think my father bought that rifle just to shut me up, and perhaps also because when he’d bought the house and contents there was a shotgun in it, which I had immediately appropriated. I imagine he felt that if he didn’t buy me a .22 I’d get that shotgun out, and that had considerably more destructive potential.

With a .22 I could shoot woodchucks on the lawn and in the garden since there was a continuous open season on them and on the family property I didn’t need a license. So that summer at age 14 I started in on them. In those days “woodchuck hunting” was a popular pastime in the Northeast and often written about in Field & Stream. Incidentally, in the northeastern USA Marmota monax is called a “woodchuck” and until I went to an Ohio college I never heard them called anything else. In Ohio and here in Virginia they’re “groundhogs.”

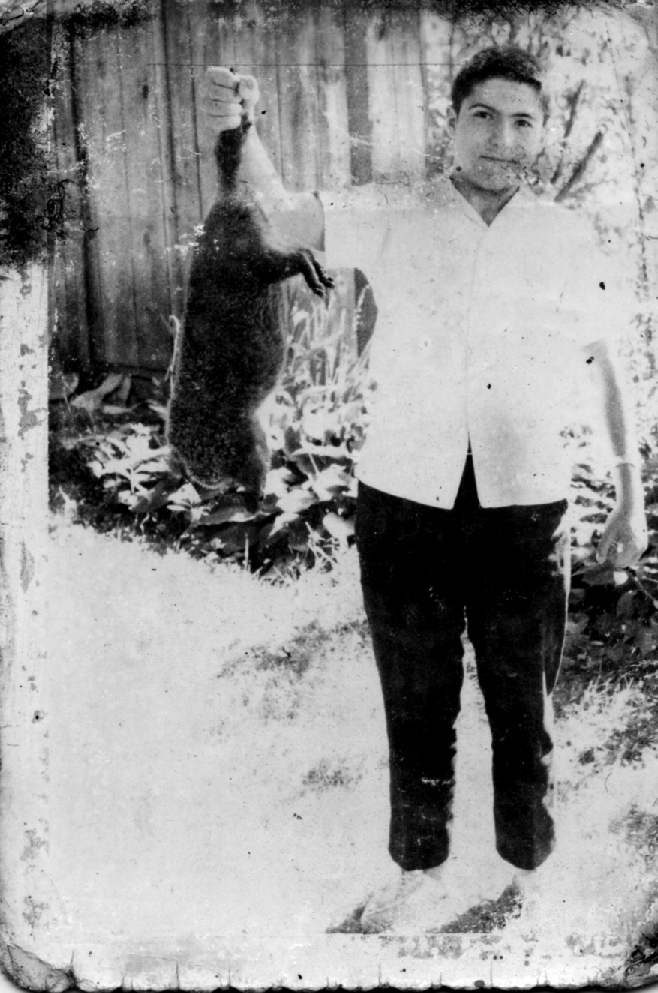

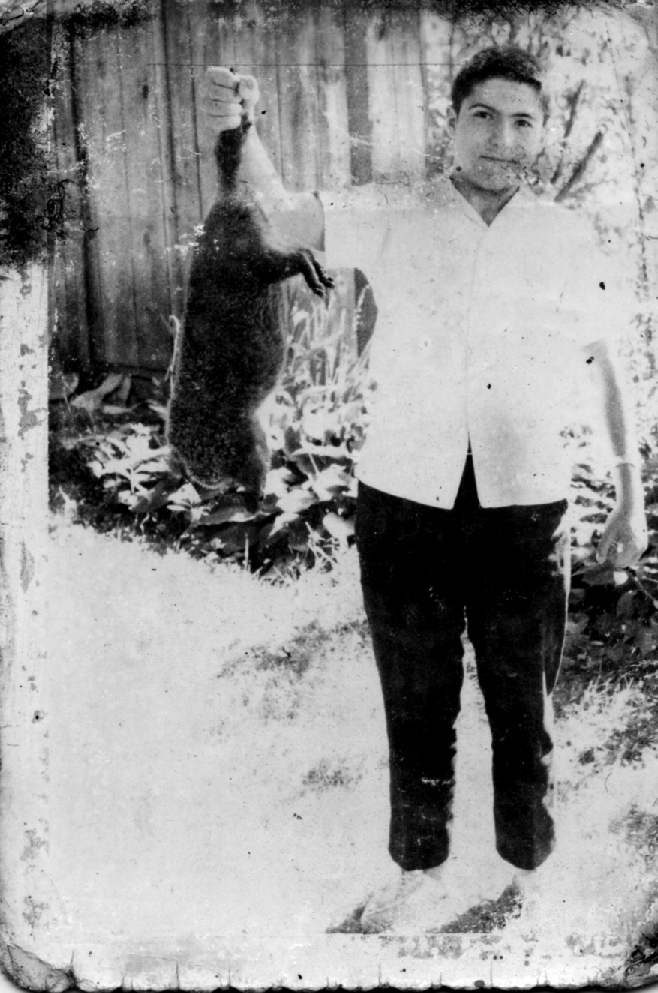

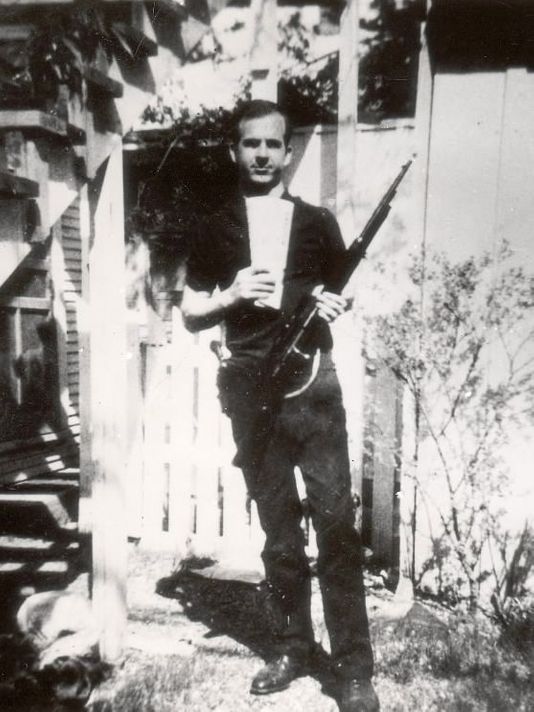

I wasn’t very good at it, but over the course of several summers I did my bit to rid the State of New York of some of these animals. Some I stalked—mostly unsuccessfully—the others I shot as “targets of opportunity” from the porch on the house. The black and white picture posted here is dated Wednesday, August 28, 1963 and is one of the first woodchucks I ever killed. I was about to start 11th Grade when the picture was taken. This animal, whom I dubbed “Old Brownie,” lived in a burrow in an apple orchard behind my father’s house. That burrow probably still exists and likely has been inhabited continuously for well over a century at this point.

I wasn’t very good at it, but over the course of several summers I did my bit to rid the State of New York of some of these animals. Some I stalked—mostly unsuccessfully—the others I shot as “targets of opportunity” from the porch on the house. The black and white picture posted here is dated Wednesday, August 28, 1963 and is one of the first woodchucks I ever killed. I was about to start 11th Grade when the picture was taken. This animal, whom I dubbed “Old Brownie,” lived in a burrow in an apple orchard behind my father’s house. That burrow probably still exists and likely has been inhabited continuously for well over a century at this point.

I learned a lot from Old Brownie. He was pretty smart and very skittish and it took me all that summer to get him, as the date on the picture proves: New York City schools traditionally open on the first day after Labor Day, so I finally made the kill only five days before I had to return to the classroom on September 2nd of that year.

If Old Brownie had the slightest inkling that people were around he’d scoot under the pine trees on a ridge behind the orchard and stay hidden for the rest of the day. So I learned that I had to figure out his patterns, which took me a while. He typically emerged very early in the day, and while I’m not (and even at that age I wasn’t) an early riser, I was determined to get him, so I forced myself to get up early enough. Shots had to be taken from a window in the house, because if I tried to sneak up on him from anywhere outdoors, off he went. Shooting from the back of the house I was hampered by an old-fashioned swing-out storm window that allowed me to take a shot only from a specific small arc. But one day things came together: I got up early, Old Brownie was in the right spot, and that  was that. Ave atque vale!

was that. Ave atque vale!

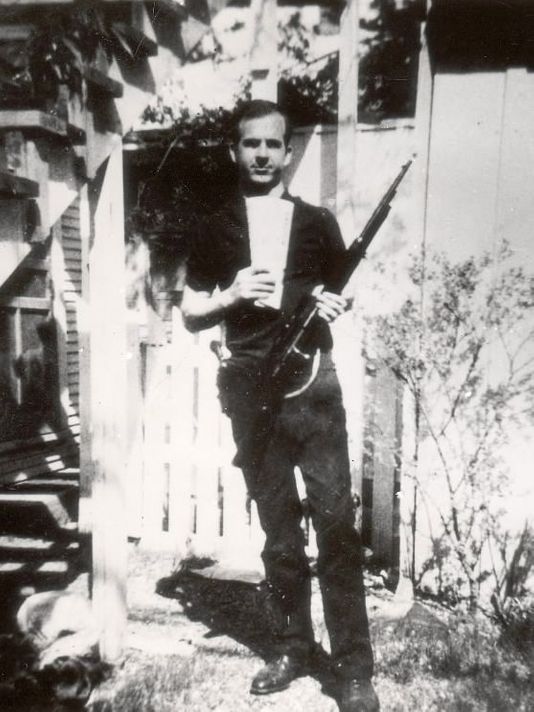

The color picture at left was taken later: while it isn’t dated it probably was during my early years in college when I went home for the summer. That would be about 1965 or 1966. In this picture I’m holding that Remington Nylon 11 rifle. I’ve  never used anything but a .22 on woodchucks except for a few I took with a shotgun, and one with a 1967 Volvo. There was a craze in the 1960’s for shooting them with centerfire .22’s (e.g., the .22 Hornet, the .222 Remington, etc.) but I had neither the need nor the money to buy such a rifle; nor would I have been able to find a place to use it safely. A .22 Long Rifle round works very well if you use hollow point bullets (the solids too often don’t kill them outright) and put the bullet where it should go for a clean kill.

never used anything but a .22 on woodchucks except for a few I took with a shotgun, and one with a 1967 Volvo. There was a craze in the 1960’s for shooting them with centerfire .22’s (e.g., the .22 Hornet, the .222 Remington, etc.) but I had neither the need nor the money to buy such a rifle; nor would I have been able to find a place to use it safely. A .22 Long Rifle round works very well if you use hollow point bullets (the solids too often don’t kill them outright) and put the bullet where it should go for a clean kill.

That was another lesson I learned shooting woodchucks: shot placement matters more than anything else, certainly more than caliber. A .22’s level of energy is enough for a 6- to 9-pound animal, but a solid bullet isn’t ideal. The hollow points kill quickly, solids don’t. I remember one woodchuck I shot on the lawn using a solid bullet: he got away to crawl under the porch and died there. The body was inaccessible and as he decayed the stench was very nearly unbearable. My father groused for years about that woodchuck and how it stank as it decomposed.

LICENSED AT LAST

I could get a small game license at 14, so more or less by default squirrels were the first real “game” I pursued. In doing so I was unknowingly adhering to one of the oldest American hunting traditions: that a kid’s first game should be tree squirrels. In frontier times, when squirrels were fantastically abundant, boys routinely hunted them for the table. There’s a legend that even Davy Crockett did this, using dried peas instead of bullets made of scarce and valuable lead. Maybe that’s true.

I could get a small game license at 14, so more or less by default squirrels were the first real “game” I pursued. In doing so I was unknowingly adhering to one of the oldest American hunting traditions: that a kid’s first game should be tree squirrels. In frontier times, when squirrels were fantastically abundant, boys routinely hunted them for the table. There’s a legend that even Davy Crockett did this, using dried peas instead of bullets made of scarce and valuable lead. Maybe that’s true.

Squirrels are about as good a “starter game animal” as could be found. The fact is that squirrels in the woods are nothing like the semi-tame ones in city parks. They’re smart, fast, extremely wary, and hunting them successfully demands a certain level of woodcraft and stalking ability. They were and are an ideal “starter” for a new hunter and it’s a shame more people don’t hunt them. I’ve actually had kids in my Hunter Ed class—kids who’ve shot several deer by the age of 9 or 10—ask me “Why would you want to hunt squirrels?”

I looked deeper into the topic of squirrel hunting. Every publication cycle Field & Stream carried at least one article on the topic; while they were pretty repetitive in content they did cover the basics well. I learned that squirrels were best found in oak woods—check: there were many oaks on my father’s place—and hunted with .22 rifles or shotguns. Check: I had both by age 14, my Nylon 11 and that single-shot 20-gauge Stevens left behind by the former owners.

I already knew from personal observation that it’s nearly impossible to approach a squirrel closely anywhere outside of a city park where they’re habituated to humans as a source of food. Even the ones in our Bronx backyard, who lived in an immense elm and raided the pear tree on the lawn, were terrifically skittish. I reasoned therefore that if I sat still and waited they might come out, so that’s what I did. When I first ventured into the woods—attired in a ghastly rubberized red “hunting coat” that was surely the worst piece of outdoor gear I’ve ever owned—I had acquired a certain level of “book” knowledge of what to do. I went into my father’s woods and waited until squirrels showed up. It worked. The squirrels came out, I killed some of them, and by default I became a siztjäger, a “sitting hunter,” a tactic I still use today and about which I’ll have more to say later in this essay. I’m still a squirrel hunter, more or less, but less so as time goes by. I’m not sure of the reasons why. I’ve actually sworn off shooting fox squirrels. They are just too appealing and comical: clowns of the treetops. Grey squirrels I will kill on occasion.

Now when I hunt squirrels I use a 20-gauge shotgun in the early season, when the trees still have leaves on them. Later, when the leaves have fallen and they run around on the ground searching for food, I'll shift to a rifle: either a .22 or a .32 caliber muzzle-loader.

DEER

In North America the pre-eminent big game animal is of course the white-tailed deer. They’re emblematic of hunting and images of magnificent bucks grace the pages of the outdoors magazines as the season approaches. Whitetail hunting is not only a major part of hunting in the USA, it’s a fairly sizable industry in and of itself. So naturally I wanted to hunt deer.

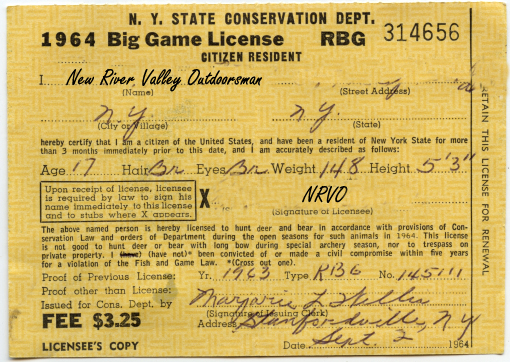

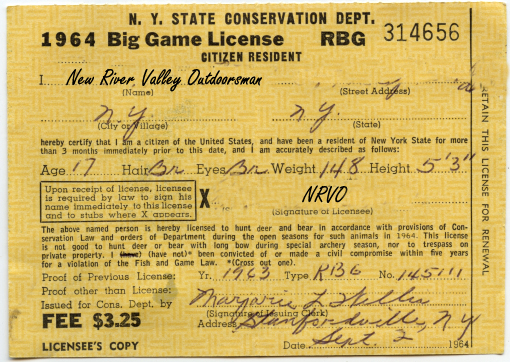

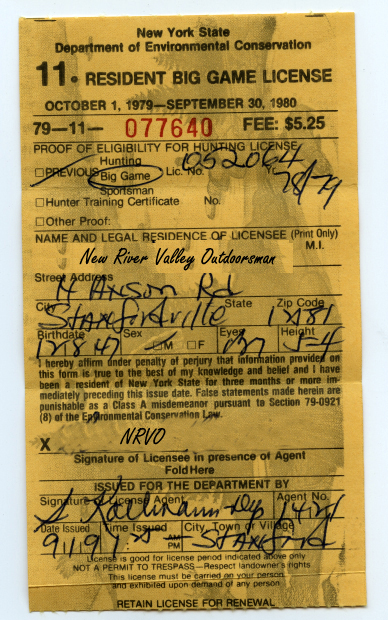

I turned 16 in December of 1963, and at that age I could get a big game license. Unfortunately the deer season was over, so I had to wait one more year. In 1964 I bought my first deer license and started my long and error-filled quest for my first deer. This took a long time to happen for many reasons, principally my own ignorance of the subject and the limited value of the books and magazines as what you might call the deer hunting “curriculum,” but there were other factors.

First, there weren’t anywhere near as many deer in Dutchess County as there are now. Today it’s thick with deer, and is in fact the epicenter of the Lyme Disease epidemic: but it wasn’t like that in 1964. In the 19th and early 20th Centuries deer had been heavily pressured by commercial market hunting, drastically reducing their numbers. I don’t know what the numbers were in New York but in 1939 the official estimate of the whitetail population in Virginia was fewer than 25,000 individuals: today it’s over a million. The North American whitetail was on the edge of extinction and would have disappeared had nothing been done.

Another factor which impacted most game species greatly was the destruction of the American Chestnut trees by a blight introduced in 1903 that spread like wildfire. By 1950 the American Chestnut was functionally extinct. Since at one time this species constituted a quarter of all the hardwood trees in North America, reliably producing edible nuts that were a major food source for game, its loss was devastating.

The conservation movement begun by Theodore Roosevelt and carried on after his death by others had come about just in the nick of time to save game populations, including whitetails, from disappearing altogether. In the mid-1930’s new laws were passed that banned market hunting, and created new sources of funds for habitat reclamation by imposing taxes on guns and ammunition and distributing them based on a state’s hunting license sales. The conservation movement also produced a generation of professional, scientific game managers. This combination of factors resulted in the restoration of whitetail deer populations from their low point, and is the greatest success story of American resource conservation, but not the only one. Waterfowl and turkeys and other game species also have recovered.

But in the early 1960’s the restoration process was still under way, not yet complete. Deer numbers had reached huntable levels years before, but they still weren’t thick on the ground anywhere in New York State. Nevertheless, I knew there had to be deer on my father’s land because that property was heavily wooded and deer live in the woods.

INTO THE WOODS

The land my father owned had been settled for a very long time. The first family to clear it and live there were the Hyatts, the first of whom came to the Hudson Valley about 1740. They established “Honey Meadow Farm,” and the house my father owned was certainly the second and perhaps the third one on that property; it was built in about 1810. The last of the Hyatts sold the property to a man named Hoffmann in 1937, and he sold it to my father in 1961.

As a working farm, the land had of course long been cleared, and there exist pictures of the place in the 1880’s showing that what I knew as woods were fields demarcated by the sort of piled-rock walls characteristic of New England and seen in Currier & Ives prints. Dutchess County may be politically part of New York but geographically, since it’s east of the Hudson River, it’s really part of New England, and it looks it. Eons ago the whole area was glaciated; as a result the soil is very rocky. Rocks come up out of the ground every Spring due to frost heaves.

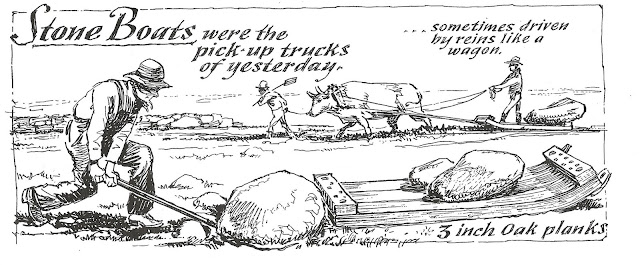

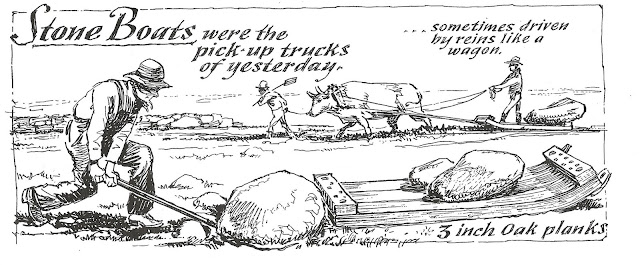

The first settlers thriftily used "stoneboats" to collect the boulders and built walls out of them, at the cost of stupendous labor. But the walls remained in place (and still do) after centuries.

The Hyatts stopped active farming no later than 1900, and the forest immediately began to reclaim the land. The Hoffmann family planted enormous numbers of trees, both conifers and hardwoods. By the time my father bought the place the natural and expedited re-forestation was well advanced to the point where there were many acorn-bearing oak trees (though alas there were no chestnuts). It was maturing woodland but not yet fully matured, the sort of environment in which deer thrive. And the deer loved those old rock walls. They constituted a series of “highways” that they used to run from place to place.

I started deer hunting in the Fall of 1964, and nobody could have been so totally clueless as was I. Every season I’d look for a place in the woods that looked “deer-y” to my untrained eye, sit down, and wait. No doubt the deer knew I was there, though, because they saw me move, heard me, or smelled me.

I started deer hunting in the Fall of 1964, and nobody could have been so totally clueless as was I. Every season I’d look for a place in the woods that looked “deer-y” to my untrained eye, sit down, and wait. No doubt the deer knew I was there, though, because they saw me move, heard me, or smelled me.

Given the relatively small deer population, the odds were very much in their favor. I occasionally caught a glimpse of one but as for killing one…forget it. Plus, at the time only bucks were legal: re-population policy mandated that does had to be protected. Right there at least half the deer population was inviolable. Nevertheless I spent as much time as I could during my late high school and college years “deer hunting,” which meant sitting in the woods on weekends during Thanksgiving and Christmas vacations. My family viewed it as harmless craziness, and the idea that I might someday actually kill a deer was so unlikely as not to be considered. They were right.

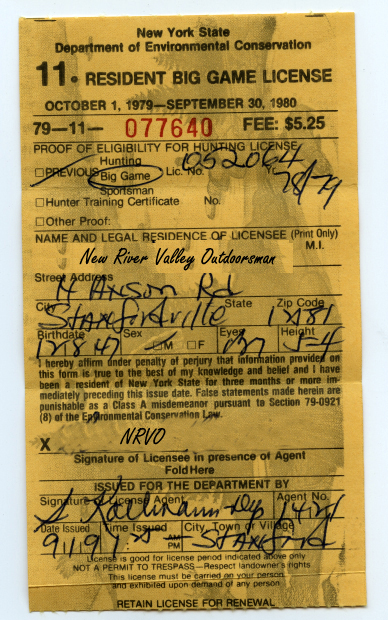

Then other forces intervened. I joined the Air Force in late 1969. Between Basic Training, Advanced Training, service in Vietnam in 1970-71, and 2-1/2 years at Andrews Air Force Base after coming home, I was unable to hunt at all until 1974. At that point I returned to the field. I married in 1975 and so did one of my sisters: her husband was a hunter and had actually killed a deer or two, so for the first time I did have some mentoring available. He and I hunted together a few times between 1975 and 1979. With his help and in his company I finally managed to get all the pieces in place and kill my first deer. I was in graduate school and married at the time, living in Washington DC, and had driven up for the opening day, leaving my long-suffering wife behind.

When the great moment happened I was nearly 32 years old. After many fruitless seasons I’d actually acquired the ability to sit stock still for long periods of time even in freezing weather. I could spend a whole day sitting on a rock in the snow, more or less immobile, for a week at a time. I used those old liquid-fuel hand warmers and later some of the really ineffective charcoal-stick variety to help me survive; I wore my very heavy USAF overcoat and several layers of clothes, sticking it out in the cold for hours on end. I can’t do that anymore and I’m very glad that I now live in a milder climate! Virginia winters can be cold but they’re nowhere near so bad as Dutchess County in late November.

When the great moment happened I was nearly 32 years old. After many fruitless seasons I’d actually acquired the ability to sit stock still for long periods of time even in freezing weather. I could spend a whole day sitting on a rock in the snow, more or less immobile, for a week at a time. I used those old liquid-fuel hand warmers and later some of the really ineffective charcoal-stick variety to help me survive; I wore my very heavy USAF overcoat and several layers of clothes, sticking it out in the cold for hours on end. I can’t do that anymore and I’m very glad that I now live in a milder climate! Virginia winters can be cold but they’re nowhere near so bad as Dutchess County in late November.

So on November 19, 1979, I was freezing my ass off in a spot I thought was a good one, basing my hunt on the idea that “There are deer in these woods; if I move around I will scare them away, so there’s no point in moving around. If I just sit here long enough one will come by and I’ll kill it.” I was right.

So on November 19, 1979, I was freezing my ass off in a spot I thought was a good one, basing my hunt on the idea that “There are deer in these woods; if I move around I will scare them away, so there’s no point in moving around. If I just sit here long enough one will come by and I’ll kill it.” I was right.

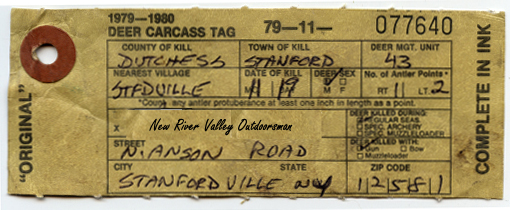

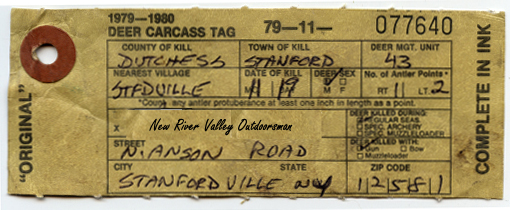

Just at dusk (on that day “Civil Twilight” ended at 5:03 PM) I heard the clatter of hooves along one of the rock walls. I looked to my right and lo, there was a deer trotting along on top of the rocks. I raised my shotgun and fired, and he fell. I was carrying a .45 caliber revolver as well; since he was still twitching I shot him several times in the neck. I now know that wasn’t necessary and that the twitching and movement of the hind legs is a characteristic of a fatal neck shot, but this was my first deer and by golly, I wasn’t going to let him get up and run off.

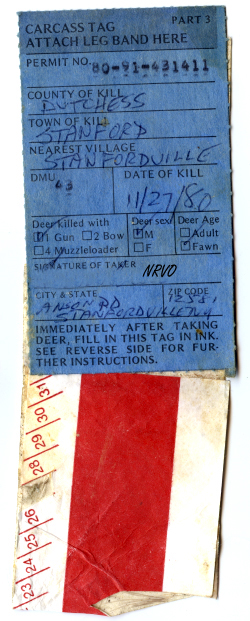

Nor did he. I walked up to him and saw it was a 3-point buck, a yearling, but I didn’t care, it was a legal deer and he was mine. I started to yell for my brother in law, because he knew what to do next and while I had the theoretical  knowledge that the deer had to be eviscerated, I had no clue how to do it. My brother in law came in response to my shouts and together we dragged the deer out, intact, to the edge of my father’s pond; a distance of several hundred yards. There we (I, under instruction) commenced the process. My first deer; that's him hanging in a tree at upper right. The extra foot is that of the button buck my brother in law killed the same day. There's a tag in my deer's ear: I've kept it as a memento mori for nearly 40 years. It's true what they say (in a different context) you never forget your first one.

knowledge that the deer had to be eviscerated, I had no clue how to do it. My brother in law came in response to my shouts and together we dragged the deer out, intact, to the edge of my father’s pond; a distance of several hundred yards. There we (I, under instruction) commenced the process. My first deer; that's him hanging in a tree at upper right. The extra foot is that of the button buck my brother in law killed the same day. There's a tag in my deer's ear: I've kept it as a memento mori for nearly 40 years. It's true what they say (in a different context) you never forget your first one.

Years before in a spirit of optimism, as part of my preparations for an eventually successful hunt, I’d bought the lovely Kā-Bar folding knife shown here at the Base Exchange at Andrews AFB. That would have been in 1971 or 1972. After seven years its time had come! I used that knife with extreme care: not only did I not want to take off a finger, I especially didn’t want to puncture any deer guts. The articles in Field & Stream on how to “field dress” a deer always laid great stress on this point. I went through that deer’s belly layer by layer, from the skin inwards, while my poor brother in law held a flashlight and griped about a) how slow I was, b) how damned cold it was, and c) would I hurry it up, already. But eventually it was done and we hung the carcass in a tree for the night. I called my wife and told her, “Better buy a freezer!”

Years before in a spirit of optimism, as part of my preparations for an eventually successful hunt, I’d bought the lovely Kā-Bar folding knife shown here at the Base Exchange at Andrews AFB. That would have been in 1971 or 1972. After seven years its time had come! I used that knife with extreme care: not only did I not want to take off a finger, I especially didn’t want to puncture any deer guts. The articles in Field & Stream on how to “field dress” a deer always laid great stress on this point. I went through that deer’s belly layer by layer, from the skin inwards, while my poor brother in law held a flashlight and griped about a) how slow I was, b) how damned cold it was, and c) would I hurry it up, already. But eventually it was done and we hung the carcass in a tree for the night. I called my wife and told her, “Better buy a freezer!”

The next day we took my deer to a processor in the village of Bangall, NY. If you could find a deer processor in Bangall today I’d be shocked: that part of Dutchess County is now a high-end exurb and commuter residential area for NY City, the kind of place where well-to-do people have weekend houses. These are mostly people who would faint at the sight of a dead deer. But in 1964 Bangall and Stanfordville, where our house was located, were genuine farm villages; and even as late as 1979 they were far more “country” than “suburban.”

I don’t remember what the guy charged, but he knocked off $5 if I let him have the hide, which of course I did. Deer hides were worth something to tanneries and I suppose he sold it on to be made into gloves or slippers. I do remember he cut it the way he thought it should be cut: that meant into very small and very thin “steaks” that were easily overcooked. When I retrieved the meat he looked at me quizzically and asked, “What the hell did you shoot it with?” It seems my enthusiastic work with the .45 had rendered the neck into mush. But I was satisfied. I had a deer for the new freezer. Things were looking up. With a scalp on my belt, so to speak, I was raring to go again. New York had a one-deer-per-season limit except in special circumstances, so I was done for 1979, but there was always next year.

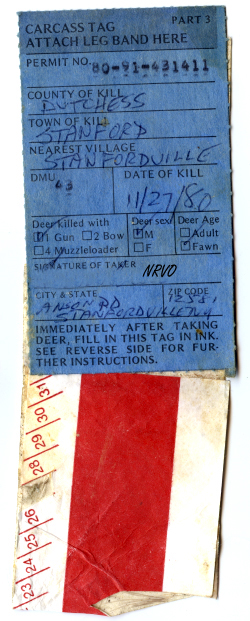

At that time NY used a so-called “party permit” system. Since the deer population was rebounding quickly, they established a rule whereby if you had a certain number of people in your hunting “party” you could get an additional coupon for an extra deer of either sex. The state was divided up into “deer management units” (DMU’s) and in DMU 43, where I hunted, until the 1980-81 season you needed to have four people in the “party.” But in that year the number required dropped to two. My brother in law and I thus constituted a “hunting party” and qualified for the extra tag. In 1980 I went back to the same spot. That's always been my pattern: find a place where things work out well and go there time after time. Over the years this strategy has worked well for me and on

At that time NY used a so-called “party permit” system. Since the deer population was rebounding quickly, they established a rule whereby if you had a certain number of people in your hunting “party” you could get an additional coupon for an extra deer of either sex. The state was divided up into “deer management units” (DMU’s) and in DMU 43, where I hunted, until the 1980-81 season you needed to have four people in the “party.” But in that year the number required dropped to two. My brother in law and I thus constituted a “hunting party” and qualified for the extra tag. In 1980 I went back to the same spot. That's always been my pattern: find a place where things work out well and go there time after time. Over the years this strategy has worked well for me and on  November 27, 1980 it did so.

November 27, 1980 it did so.

A button buck (left) came by and I shot him, filling the “party permit” extra tag. The tag is visible on the deer's leg: the law required it be attached to show the deer was taken legally. We hung him in a tree and the next day I cut him up myself, the first time I'd tried doing that job. Having been deeply dissatisfied with the results on the 1979 deer I was determined I could do better: I drove to the Agway store in Stanfordville and bought a small Disston meat saw for the job. I did not, in fact, do a very good job, but it was free. I still have that saw and I use it every year to cut a deer, nearly 40 years later.

INTERREGNUM IN EXILE

I graduated from Georgetown in the Spring of 1980 and for a couple of years I'd had a post-doctoral position at the George Washington University Medical Center. My wife and I bought a small unfinished cabin in Orange County, Virginia late in 1980, but it was too late to go hunting. We spent the Spring and Summer of 1981 working on the cabin but finally in the Fall of 1981 I got my first Virginia hunting license. I had my own woods (my father had sold his place) which though not very promising, did have deer in them, as well as squirrels. So that November I found a likely-looking spot, took my rifle (at the time, a Model 1898 Mauser) and sat down. You couldn’t hunt on Sunday in Virginia then (a stupid law that has since been more or less repealed) so I had exactly one day a week when I could get out. I went hunting to no avail: I never laid eyes on a deer in those woods, though some time in the Spring of 1981 a nice buck, still in velvet, had bounded across my front lawn and raised my hopes.

Then the necessity of earning a living interrupted my hunting life. In mid-1982 my post-doc expired and there was small prospect of finding a job in Washington thanks to Jimmy Carter’s “hiring freeze” so I had been looking elsewhere. A job came up at Texas A&M University’s veterinary school in College Station. I knew not much at all about Texas but people kept assuring me it was a great place to live and that it was a great place to go hunting, so I was hopeful, though with trepidations. I’ll pass over that period of my life quickly except to say that the finest thing I have ever seen was Texas in my rear-view mirror; I hated every square inch of the place and every second I spent there. I could go on for three days on this subject but I’ll spare my readers the agony.

One of the many disappointments I had was that in Texas if you want to hunt you have to pay a “lease” fee. I can’t expound here on the fundamental evil that “hunting leases” represent, but I’d never heard of such a thing and was shocked to the roots of my hair when I found out about them. As a matter of principle I refuse to pay any private person a fee to hunt a native game animal that is—as is true in every state, including Texas—public property. So for five long years I was more or less compelled not to hunt. I did get out twice thanks to the kindness of a friend who owned a few acres: once I killed a squirrel so infested with “warbles” (botfly larvae) and tapeworms I threw the carcass away rather than eat it; and once I got to sit in a tree overlooking a parched field with no deer in it because no deer would have been crazy enough to try to find something to eat there.

I fled the Lone Star State in early 1987 and came back to Virginia with my wife and two wonderful dogs who have long since died and I’m happy to say that for that whole five years in exile I had actually managed to retain my Virginia residency and driver’s license.

CARRY ME BACK TO OLD VIRGINIA

We arrived in beautiful southwestern Virginia in March of 1987, where I was delighted to find that there are 2,000,000+ acres of public land in the Commonwealth on which I could hunt. I did so, and did reasonably well on small game, but deer still eluded me. One drawback to public land is that it’s public, and any place that’s a good hunting spot is well known to the local hunter population: sometimes I’d arrive at the place I wanted to be and find that it was the place someone else wanted to be. I also tried my hand at waterfowling with a neighbor, but after nearly dying once I gave it up. I fell into the New River in December of 1990 and had I not been with other people I’d have died of hypothermia for certain.

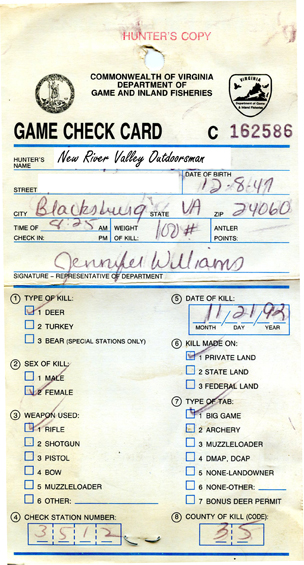

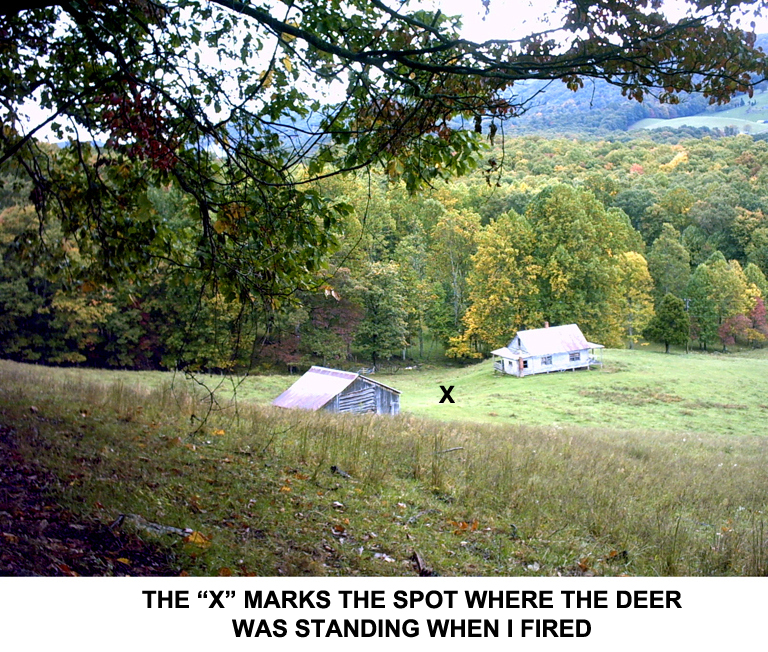

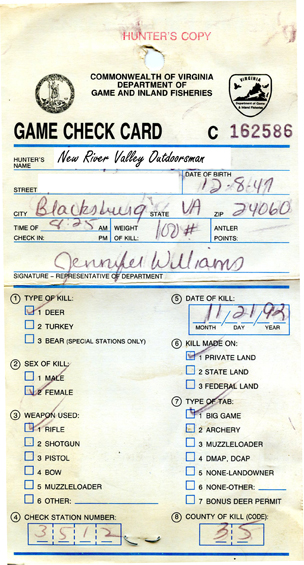

But eventually I found places to hunt on private land, by “networking” my friends, neighbors, and hunting contacts. On November 21, 1992 I managed to bag my first Virginia deer. I was hunting a farm in Giles County, a place my waterfowling friend and neighbor had told me about and whose owner was happy to give me permission (without a fee, I might add). At about 7:25 AM I was sitting on the side of a hill underneath the root ball of a tree that had been toppled by 1989’s Hurricane Hugo. I was watching a field below me when a big doe, followed by two smaller deer—undoubtedly her twin fawns—came wandering by. I fired at the doe from a sitting position, using the .30-30 barrel on a combination gun I owned at the time. The bullet hit her behind her left shoulder, exited through her right side, taking with it most of her right humerus. That's her, above right, hanging in my garage.

But eventually I found places to hunt on private land, by “networking” my friends, neighbors, and hunting contacts. On November 21, 1992 I managed to bag my first Virginia deer. I was hunting a farm in Giles County, a place my waterfowling friend and neighbor had told me about and whose owner was happy to give me permission (without a fee, I might add). At about 7:25 AM I was sitting on the side of a hill underneath the root ball of a tree that had been toppled by 1989’s Hurricane Hugo. I was watching a field below me when a big doe, followed by two smaller deer—undoubtedly her twin fawns—came wandering by. I fired at the doe from a sitting position, using the .30-30 barrel on a combination gun I owned at the time. The bullet hit her behind her left shoulder, exited through her right side, taking with it most of her right humerus. That's her, above right, hanging in my garage.

She leaped and ran, hit a wire fence, bounced off, and that was that. I paced off the distance at roughly 100 yards. This was my first Virginia deer, and a good one she was. I butchered her myself, using that little Disston saw I’d bought years before. The net yield was 50 pounds, half her hanging weight of 100 pounds. So thirteen years after my second deer, I had my third. That kill really started things going. Since then I’ve been averaging 2-3 deer per season.

Along the way I’ve honed my technique—if I may call it that—and have figured out how to make kills with reasonable regularity, though getting to this point has not been without mistakes and blown opportunities.

THE SITZJĀGER STRATEGY

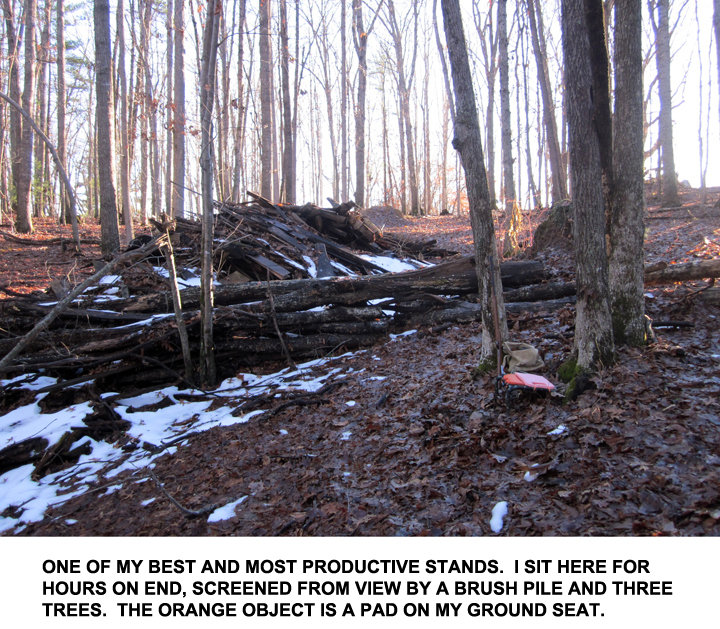

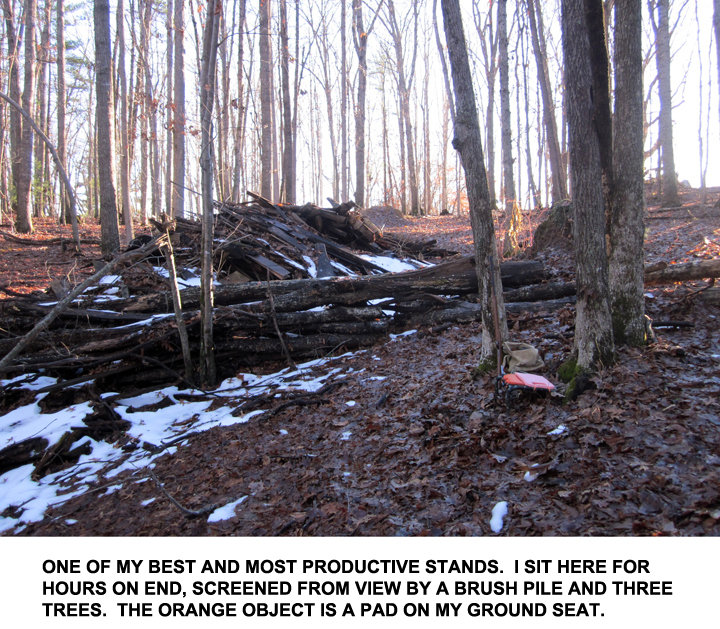

In the course of the last half-century I’ve come to some conclusions about the tactic of sitting down and waiting. That’s what the magazines call “stand hunting,” as distinct from slowly walking through the woods and watching (“still hunting”) or the “spot and stalk” method commonly used in the Western US and in Africa. I’ve used both of those other methods with reasonable success, but under the conditions in which I usually hunt, sitting on the ground and waiting has been by far the most productive approach. In fact, if you have the time to devote to it, stand hunting nearly always works. You might have to wait a long time, but in the end it will pay off.

ODDS AND ENDS OF GEAR

In the image above, you can see my little hunting stool. This is made by H.S. Strut and is the single most valuable piece of hunting gear I have besides my gun. It allows me to sit a few inches above the ground so that I don't get my ass wet; and it makes it a lot easier to get up and on my feet. Getting down is not an issue, getting up is. At my age I need all the help I can get. I don't like to have anything in my hands except my gun when I go into the woods: you can't see it here but the stool has a strap on it, and moreover I've rigged up a couple of short cords to attach it to the day bag you see next to it. That bag is another invaluable item: it's been to Africa with me three times and I never go into the woods here in the USA without it. It's actually a piece of British military surplus web gear; it holds everything I need for a day in the field. I'm long past the point of camping out, and I deeply dislike the idea of a backpack. This bag gets slung over my shoulder, leaving my hands free.

I use a sling on all my guns—shotguns as well as rifles—but I use the quick detachable kind so I can take it off when I sit down. A sling is great for carrying a gun but it's an infernal nuisance when I try to shoot, and its movement as the gun is raised can alert a deer.

And by the way, I don’t use a tree stand. Tree stands are the single most dangerous piece of hunting gear that exists, far more dangerous than firearms. As a Hunter Ed instructor I see the yearly statistics on accidents: fatalities and serious injuries from tree stand falls are far more common than from shooting accidents. I know a trauma surgeon in Roanoke who can tell you some real horror stories about such injuries. And I had a colleague who fell from his treestand and broke his back: he has been paralyzed from the chest down for more than 25 years. He's a surgeon too.

Furthermore, I contend that not one fall in ten is actually reported: only those in which an injury sends someone to the Emergency Room (or the morgue) come to the notice of the public. If you never go up in a tree stand you will never fall out of one: and I never go up in a tree stand. No deer is worth the risk.

Here’s why I think stand hunting works so well. Most importantly, I go into areas where I consistently see whatever I’m hunting for, especially deer. Most game animals, including deer, are creatures of habit. If I see them a few times in a specific area I can begin to sort out in my mind where they’re going, where they came from, and why they move where and when they do. No animal, least of all a deer, wanders around aimlessly. They know exactly where they are, exactly where they want to be, and exactly how they want to get there. Watching them walk through the woods, especially in groups, makes plain that they’re doing so with a purpose in mind, be it feeding or reproduction or something else.

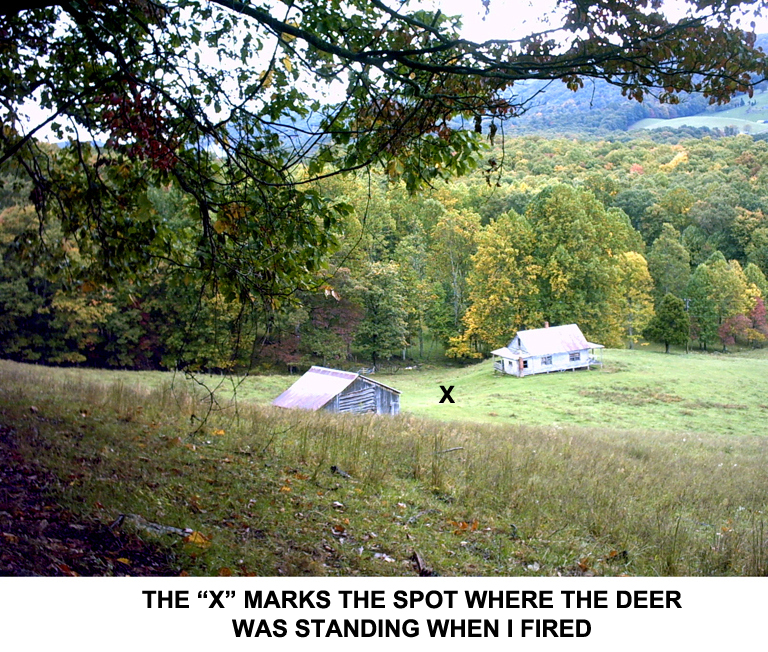

Once the process of figuring out whence they came and whither they’re headed is completed—it’s never really “complete” because there are always exceptions—it’s possible to put myself in the right place at the right time. This takes a while, though. If I come to a new hunting location or if there's some sort of major change in the terrain it will take me a couple of seasons to sort things out, but after that it’s relatively easy to predict time/location and interceptions. I once hunted a farm on which I could tell you within ten minutes and ten feet where the deer would emerge, but it took me a decade to get to that point.

Another reason why stand hunting works, I’m convinced, is that most prey species have an in-built, hard-wired mental image of what is dangerous. Some things that signal danger are obvious, such as noise or movement. But in particular a certain “aspect ratio,” the ratio of height to width, seems to be a crucial criterion for them to assess a risk. A standing man is several times higher than he is wide, and this seems almost always to be a signalment of danger. But if I sit down, and especially if I sit against a tree or other obscuring object, I change my aspect ratio and I’m no longer immediately perceived as a threat, especially if I’m immobile and noiseless. At worst even if the animal does see me, often it will hesitate and try to figure out what I am; those few seconds of indecision have cost many a deer its life at my hands. A couple of examples from this past season will suffice to illustrate this point.

Curiosity doesn’t only kill cats. During the early black powder season I was sitting in a favored spot, one where I’ve seen many deer and killed more than a few. I spotted a small doe about 30 yards off, and took the shot. I missed. The deer—obviously very naïve and very curious, watched me reload my rifle! Now, it takes a bit of time to reload a muzzle loader, especially if you have been dumb enough to leave the ball starter at home: but I managed, and after perhaps three minutes of frantically going through the motions I got a second shot which killed the deer.

Later, during the rifle season I was sitting on a hillside watching a pasture at a point where I knew deer crossed. While I was looking to my right, I heard a deer snort: I looked to my left, and there was a big doe, not 40 yards away, staring straight at me. Now, I was in clear view, but I was sitting down, and while she was suspicious and had been alerted, she was still unsure what was going on. She hesitated about three seconds, long enough for me to get the gun up, and that was her undoing.

It’s not only deer that do this. Some years ago I hunted groundhogs on a farm where there was a very large oak tree in the middle of a field, the only tree for a hundred yards around. Under that tree was a groundhog den, which no doubt had been in use for half a century or more by several generations of groundhogs. If I tried to stalk them the groundhogs went to earth and stayed there. So I took to openly walking into the field with my shotgun as if I had purely pacific intentions, parking my butt on the ground in plain view fifteen or twenty yards away from the entrance to the den. If a groundhog had scuttled down into the hole and then nothing happened, eventually he’d become curious (or perhaps forgetful). Within fifteen or twenty minutes, he’d stick his head up to have look around.

Those groundhogs had to have been able to see me: they have very good eyesight and I was quite close because a shotgun is a short range weapon. But I was sitting down, and therefore not perceived as dangerous even by an animal that’s preyed upon constantly by dogs, coyotes, bobcats, hawks, owls, you name it. After one or two trial peeks, the groundhog would decide there was nothing to be worried about: I was likely a new rock or something. He’d emerge and get killed. I did this trick many times because as soon as one groundhog died another would move into the vacated den and I’d come back a few days later. I killed five animals out of that den in a week one season.

CAMOUFLAGE AND SCENT CONTROL

The hunting gear catalogs lay great emphasis on camouflage clothing and scent blockers and similar things, but I don’t think those things matter very much except to people who make money selling them. More than once I’ve had deer come past me close enough to touch—one nearly stepped on my leg before I shot him—and this would happen even when I was covered in blaze orange. Again, if I sit down, remain motionless, and the wind is right, they simply don’t know I’m there. Invisibility is mainly a matter of immobility and silence, not what kind of camo you wear. When I'm doing my justly celebrated imitation of a tree stump, I can't even see myself.

The wind does matter, of course. While stalking you have to be aware of the wind at all times, but on a stand you just have to keep in mind that everywhere is upwind of somewhere else, and there’s nothing you can do about it. A deer downwind is going to scent you, period, no matter what you do: no cover scent or carbon-impregnated clothing can prevent it if the wind is in his favor.

I always try to sit so that the wind is in my face, or at least on one side. Deer will approach with the wind behind them or, if they need to get somewhere that prevents them from doing that, they’ll come in across the wind. I watch the upwind or crosswind direction for movement. Since I can’t move around it's important to pick a spot where I can predict the way the wind will blow. In the morning, breezes move uphill as the ground warms, so it pays to sit on a hillside and watch the area below my level. Animals below me can’t smell me and they can’t see me. Not too infrequently the configuration of the site offers advantages.

I have one spot I call “The Rock.” A very large flat rock sticking up out of the ground looks down on a trail below. The flat rock behind me serves not only as a convenient back rest, it creates a visual screen and a wind shield. Deer below me can’t make me out. Deer behind me can’t see me at all. And if there’s a breeze, either up or down hill, the rock interferes with the flow of air. With an uphill breeze there’s a “burble” where it meets the rock, causing my scent to be deflected back downward and away from the trail behind me. If there’s a downhill breeze I’m sitting in the “wind shadow” and my scent isn’t carried to the trail below. I’ve lost count of how many deer have been killed from this spot.

I have one spot I call “The Rock.” A very large flat rock sticking up out of the ground looks down on a trail below. The flat rock behind me serves not only as a convenient back rest, it creates a visual screen and a wind shield. Deer below me can’t make me out. Deer behind me can’t see me at all. And if there’s a breeze, either up or down hill, the rock interferes with the flow of air. With an uphill breeze there’s a “burble” where it meets the rock, causing my scent to be deflected back downward and away from the trail behind me. If there’s a downhill breeze I’m sitting in the “wind shadow” and my scent isn’t carried to the trail below. I’ve lost count of how many deer have been killed from this spot.

On this matter of blaze orange, I’m sure deer simply can’t see it, and even if they can see it, it means nothing to them. Squirrels, on the other hand, not only can see it, they’re attracted to it. Grey squirrels especially are very curious about new things in their environment, and a sitting man in blaze orange is something they want to investigate. They’re as likely as not to come and sit on a branch or a log quite close to me, and check me out; sometimes they get excited and start chattering and stamping their feet to try to make me move.

I do wear blaze orange. It just makes sense, and besides it’s the law. I have no desire to be shot nor to shoot anyone else. One significant drawback to blaze orange is that while it undoubtedly has saved many, many lives, it tends to inculcate a mindset that “If it’s not blaze orange I can shoot it.” People who don’t use it are really almost “asking for it,” and while there’s no excuse for anyone to take a shot if he’s not absolutely sure his target is a valid one, it does happen. It happens to the sort of people who say, “Heck, I don’t need that, I’m on private land!” How do I know this? In the annual accident reports I see “mistaken for game” shootings invariably involve someone who wasn’t wearing blaze orange when he should have been.

WHERE I HUNT

I hunt in thick woods most of the time. Ranges are short: a 50-yard shot is a very long one and most are within 30 yards. Often they’re measured in feet, not yards. Last season I shot a doe at all of 11 yards, and I’ve killed a couple who were closer than that. This of course affects the choice of hunting equipment: some of my guns would be not well suited to hunting in the American west where ranges tend to run 200 or more yards, but in the dense woods of Virginia what I hunt with works very well. Only a few times have I had shots of 100 yards or more. I’d never try such a shot with iron sights but I’m comfortable with one using a scoped centerfire rifle.

I hunt in thick woods most of the time. Ranges are short: a 50-yard shot is a very long one and most are within 30 yards. Often they’re measured in feet, not yards. Last season I shot a doe at all of 11 yards, and I’ve killed a couple who were closer than that. This of course affects the choice of hunting equipment: some of my guns would be not well suited to hunting in the American west where ranges tend to run 200 or more yards, but in the dense woods of Virginia what I hunt with works very well. Only a few times have I had shots of 100 yards or more. I’d never try such a shot with iron sights but I’m comfortable with one using a scoped centerfire rifle.

I used to hunt a farm with a long pasture. There were hills on one side and a rocky outcropping on the other side where I’d sit. This was another place where the geography was in my favor. Winds were very predictable: they blew along the long axis of the pasture because the configuration of the land prevented any cross winds. Furthermore that rocky outcropping had a scooped out section that provided a convenient wind shield. I was un-scentable and invisible. One day I shot a buck trotting along on the far side of the pasture from my right to my left: I paced off that distance at 106 yards. Other than the first deer I killed in 1992, a doe at a similar distance, that was the only time I can recall such a long shot. I have no doubt I can kill a deer at 200 yards if the chance presents itself during rifle season, but it never has yet.

BIRDS

We don’t have much wingshooting in the part of Virginia where I live. A few doves if you know where to go, and that’s about it. Every year I go out with some friends and do a put-and-take shoot for pheasant and quail in Franklin County. For a while I had access to a farm where I could shoot feral pigeons flying in and out of a silo, but that spot dried up. Pigeons were great fun, but they’re not very abundant in this part of Virginia except under highway overpasses and the State Police take a dim view of shooting along highways.

Before I gave up waterfowling I did manage to hit some ducks and a goose or two. But after plucking a couple of Canada geese, I decided it wasn’t worth the effort: if I want to eat a goose these days I go to Kroger’s and buy a frozen one.

Before I gave up waterfowling I did manage to hit some ducks and a goose or two. But after plucking a couple of Canada geese, I decided it wasn’t worth the effort: if I want to eat a goose these days I go to Kroger’s and buy a frozen one.

Ditto ducks. The risk to life and limb, not to mention the expense of even the minimal kit needed for waterfowling—$1000-2000 if you buy any kind of a boat (even a canoe) and the fact that in a really good season you might kill five ducks—means it simply isn’t worth it. Once I did get to go to Argentina: a place whose abundance of birds is almost incomprehensible until you see them. In those few days I did more wingshooting than I had ever done before and more than I will ever do again unless I go back.

I’m not a very good wingshot. When I’m “in the groove” I can hit 40% of the birds I shoot at. My preference is for pheasant, they’re big enough I have some chance of hitting them. I don’t use “magnum” shotshells, the standard 2-3/4” length is good enough. I've killed some with a muzzle-loading shotgun, too!

AFRICA

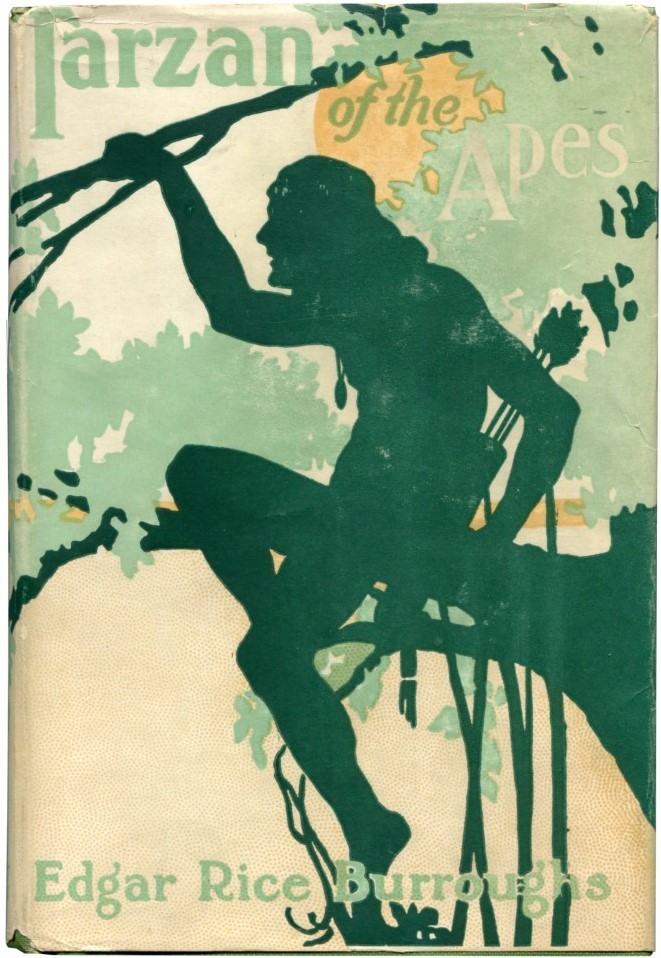

The contents of the house my father bought in 1961 included a sizable library. In this were a couple of books in the “Tarzan of the Apes” series, and these fired my desire to hunt in Africa. I was unaware that Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Africa was wholly the figment of his imagination, and I wouldn’t have cared had I known. Burroughs set my mind onto the subject and I vowed that someday I would hunt Africa. I have done so three times and would very much like to do it again, but whether I’ll be able to do so at this stage of my life is problematic. I went to the Republic of South Africa in 2004 and to Namibia twice, in 2010 and 2013. In Africa spot-and-stalk is the primary method of hunting and I discovered I’m pretty good at it. I once actually stalked a whitetail, but he was very young, very naïve, and extremely stupid and he doesn’t count, really. But I was able to sneak up on a couple of wildebeest and some other antelope; and I have to pat myself on the back and say that in 2013 I did a fine stalk to within 40 yards of the elephant shown above. Standing with me is my guide and PH, Cornie Coetzee.

The contents of the house my father bought in 1961 included a sizable library. In this were a couple of books in the “Tarzan of the Apes” series, and these fired my desire to hunt in Africa. I was unaware that Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Africa was wholly the figment of his imagination, and I wouldn’t have cared had I known. Burroughs set my mind onto the subject and I vowed that someday I would hunt Africa. I have done so three times and would very much like to do it again, but whether I’ll be able to do so at this stage of my life is problematic. I went to the Republic of South Africa in 2004 and to Namibia twice, in 2010 and 2013. In Africa spot-and-stalk is the primary method of hunting and I discovered I’m pretty good at it. I once actually stalked a whitetail, but he was very young, very naïve, and extremely stupid and he doesn’t count, really. But I was able to sneak up on a couple of wildebeest and some other antelope; and I have to pat myself on the back and say that in 2013 I did a fine stalk to within 40 yards of the elephant shown above. Standing with me is my guide and PH, Cornie Coetzee.

OF BALLISTICS

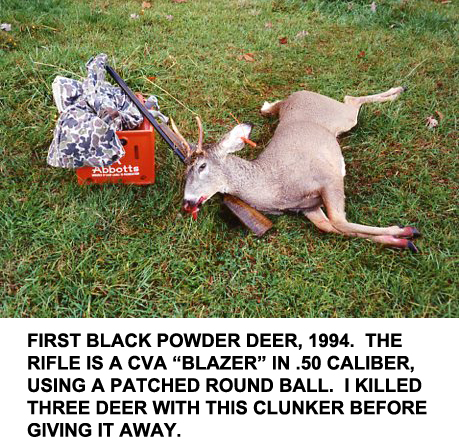

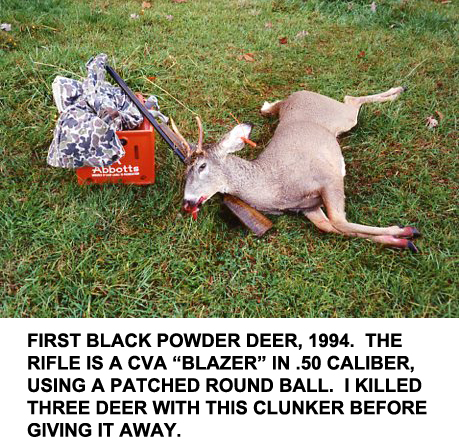

Ninety-nine percent of American hunters believe that muzzle velocity is the prime determinant of a rifle’s effectiveness, hence the popularity of very high-velocity “magnum” calibers. This belief extends to muzzle-loading rifles as well. Ninety-nine percent of Americans who hunt with muzzle-loaders use a .50-caliber in-line loaded with light conical bullets and heavy powder charges to attain maximum velocity. But this belief is wrong. While on paper black powder rifles have “modest” ballistic performance, there is no doubt that a big fat round ball at moderate velocities can do what needs to be done. In any event, no muzzle-loader using black powder or a “replica” powder is going to break 2000 feet per second muzzle velocity. Most will be doing very well to hit 1800 FPS.

The principle that heavy bullets at moderate velocity work well is true for centerfire rifles as well as muzzle-loaders. The notion that eye-popping velocity and paper energy numbers are “better” is intuitively attractive but demonstrably false. There’s nothing in North America that can’t be reliably killed with a .30-06 or a .308; the Super-Duper Hot-Shit Magnum calibers are fun but they’re simply unnecessary. They have a lot of flash and bang but no more effectiveness on game than boring old stuff like the .30-06. Our local deer average 110-120 pounds or so: the biggest bucks might go 200 pounds on the hoof at a stretch. My old reliable .30-06 Savage 110 (bought at a fire sale price in a close-out at a Roanoke discount store) has done yeoman service in the US and in Africa as well. A few years ago I won a beautiful Kimber rifle in .308 caliber in a raffle, and have used it successfully in the seasons since. There isn’t a deer in the Commonwealth that can’t be taken cleanly with either of these calibers. Even a Virginia black bear is susceptible to their blandishments. I hasten to add that while I’ve seen bears in the woods, I’ve never killed one, have no desire to kill one, and would not do so except in self-defense.

I do own one large-caliber centerfire rifle, a .416 Remington Magnum I’ve used exactly once. Though it’s a real bruiser and firing it makes me feel like I’ve accomplished something, it’s no speed demon: a 400 grain bullet at 2400 FPS qualifies as a “Magnum” by any definition but its real virtue is penetration because of that very heavy bullet.

Another caliber I like and use a great deal but that generates merely "ho-hum" responses in the gun press (when it gets mentioned at all except as an afterthought) is the 8x57mm Mauser. As loaded in the USA it’s underpowered, but in the European loadings it’s easily the equivalent of the .308 Winchester in performance and effectiveness. The biggest non-pachyderm animal I’ve ever killed was a 1900-pound Livingstone Eland (the largest antelope in Africa) taken with an 8x57 using Norma’s “Alaska” ammunition: a 196-grain round nosed bullet at 2526 FPS and 2778 FP of energy. He went 30 yards after being hit and dropped.

Another caliber I like and use a great deal but that generates merely "ho-hum" responses in the gun press (when it gets mentioned at all except as an afterthought) is the 8x57mm Mauser. As loaded in the USA it’s underpowered, but in the European loadings it’s easily the equivalent of the .308 Winchester in performance and effectiveness. The biggest non-pachyderm animal I’ve ever killed was a 1900-pound Livingstone Eland (the largest antelope in Africa) taken with an 8x57 using Norma’s “Alaska” ammunition: a 196-grain round nosed bullet at 2526 FPS and 2778 FP of energy. He went 30 yards after being hit and dropped.

A variant of the 8x57 is the rimmed version used in combination guns and drillings, the 8x57JR (at right). This is dimensionally the same as the round for bolt-action rifles, except for having a rim suitable for the extractor of break-open actions. Only one company (Sellier & Bellot) still loads it, but their loading is wonderfully effective. That 196 grain jacketed soft point moving at a leisurely 2329 FPS may cause snickers from the faster-is-better-and-don’t-you-ever-forget-it crowd, but it works a treat. I’ve killed three deer, a couple of big feral hogs, a large male ostrich, and numerous black-backed jackals with it and never needed a second shot. It kills whitetails like a bolt of lightning.

A variant of the 8x57 is the rimmed version used in combination guns and drillings, the 8x57JR (at right). This is dimensionally the same as the round for bolt-action rifles, except for having a rim suitable for the extractor of break-open actions. Only one company (Sellier & Bellot) still loads it, but their loading is wonderfully effective. That 196 grain jacketed soft point moving at a leisurely 2329 FPS may cause snickers from the faster-is-better-and-don’t-you-ever-forget-it crowd, but it works a treat. I’ve killed three deer, a couple of big feral hogs, a large male ostrich, and numerous black-backed jackals with it and never needed a second shot. It kills whitetails like a bolt of lightning.

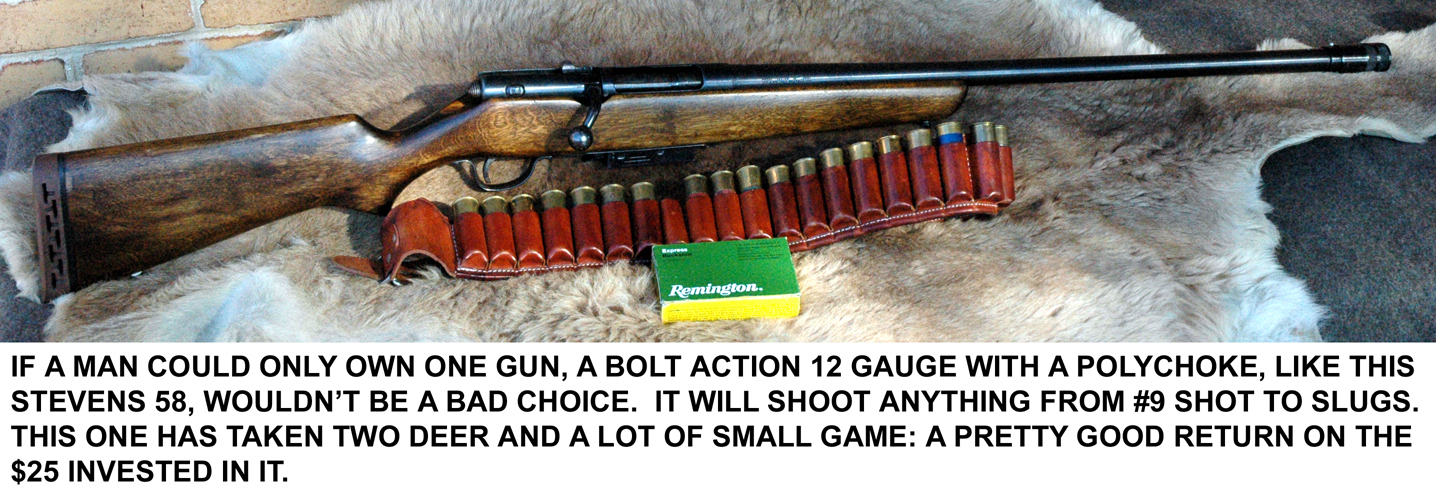

New York required shotguns to be used in Dutchess County and my first two deer were taken with Foster-type slugs from a bolt action 12 gauge. That too kills them without any fuss; an ounce of lead at 1100-1200 FPS is more than enough power for any deer: put it forward of the diaphragm and the deer isn’t going anywhere. Bottom line: heavy-for-caliber bullets just plain work, no matter what you’re hunting or hunting with.

OF SIGHTS AND SCOPES

On the matter of sights, I’ve mentioned that my black powder rifles have iron sights. I long ago abandoned the use of “open” sights: my old eyes can’t focus on a rear notch, a front bead, and a target at the same time. A peep sight, however, still works pretty well for me. Looking through the rear sight my eye is automatically centered and I can see the front bead reasonably well. No doubt there will come a time when even peep sights can’t help my deteriorating vision, but that time isn’t yet. In the woods, at my normal ranges, peep sights still work.

Of course on “regular” centerfire rifles I use a scope. In a way it would be irresponsible not to: scopes do make it easier to put the bullet precisely where it needs to be to effect a clean kill, and a scope extends the effective range at which I can take an ethical shot. All my centerfire rifles are fitted with scopes. Even though I hunt in places where ranges are short, I’d have no hesitation in taking a shot with one of these rifles that I’d pass up with an iron sighted one.

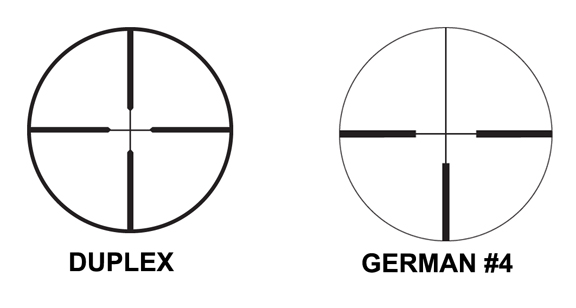

I don’t like variable power scopes: they’re a solution in search of a problem. My Nylon 11 had a fixed 4x scope (a Weaver B-4, a real dinosaur now) so by preference I’ve stuck with fixed power scopes to this day. For 90+% of the shots I’ve taken, 4x has been quite enough magnification. One rifle has a fixed 6-power scope and that works well, too. There isn’t much difference between that and 4x.

I like fixed-power scopes because they’re lighter, mechanically simpler, and far less likely to shift point of impact than any variable. I’ve never felt comfortable with the idea of sighting the gun in at one power and then changing it to use in the field. Today the “normal” scope is a 3-9x variable (try to find anything else in the catalogs!) and people I know who use these will sight in at 9x and then lower the magnification to hunt, sometimes cranking it up again when the target is spotted. This has always seemed unwise to me. Even with a very well made scope, there has to be some variability in the point of impact between powers just due to the necessary machining tolerances of the mechanism. When you factor in normal wear and tear over the seasons, that has to affect point of impact as well. Granted it may not be by much, and that an inch or two change in POI isn’t going to matter to the deer that gets shot, but it’s still a bothersome notion. I do have variable-power scopes on some guns, because in those cases I couldn’t find a good quality fixed power scope with the type of reticle I like. With variables I simply set the ring at 4x (perhaps 5x), sight it in, and leave it alone thereafter.

I buy mainly Leupold products, though not exclusively. They’re very good quality instruments with excellent optical clarity, but they don’t cost the earth, as Zeiss or Kahles scopes do. If I could afford top-end optics I’d buy them, but while I can justify $400 +/- for a decent scope, no way can I do so for an instrument that costs $3000-4000. I wish I could.

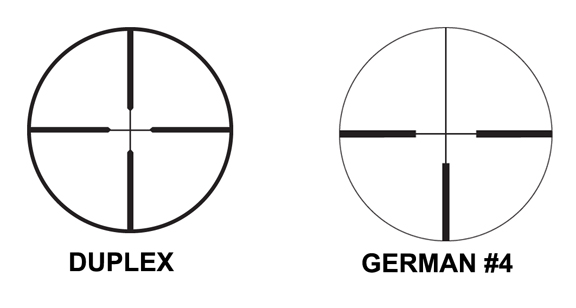

When it comes to reticles, I used to prefer simple thin crosshairs, but that’s something almost impossible to find in mass production scopes for centerfire rifles. The so-called “duplex” reticle is by far the most common type: its crosshairs are thinner in the center than on the sides. I don’t really like these, I feel they’re less precise than a fine crosshair, but I’ve learned to use them. Two of my rifles have fixed power scopes with duplex crosshairs.

What I really like is what’s called a “German #4” reticle. This is a European style rarely seen on American scopes, but it can be had on special order through Leupold’s Custom Shop. The German #4 has the virtues of being very easy to see, allowing quick target acquisition, and more or less instinctive centering. Coupled with good quality glass it’s hard to beat, especially in dim light.

I’ve not got much use for illuminated reticles, but I generally don’t hunt at night; if I did I might find them useful. As it is I can take them or leave them. I had an IR scope once and never turned it on. A red dot sight is another matter. I put one of these on a dangerous game rifle and it’s fast in action and very reliable. The only drawbacks are that if the dot is too bright it can obscure some of the target—not an issue on an elephant at 40 yards—and that the dot subtends some 3-4 minutes of angle, which makes red dots not too precise compared to a scope. In general I don’t have much use for scoped handguns, but I have one Ruger pistol with a red dot scope on it that is essentially a Squirrel Death Ray. Put the dot on the squirrel, pull the trigger, and down he comes.

HOW ACCURATE DOES IT HAVE TO BE?

I know several shooters and hunters who are obsessed with rifles that shoot the smallest possible groups, and who will spend inordinate amounts of money trying to get a rifle to shoot to their standards of perfection. In most cases, the minimum acceptable performance is 0.5 MOA (half-inch groups at 100 yards) and these friends will spend weeks trying new handloads, changing bullet weights, using different powders and primers, etc., constantly tweaking things in the pursuit of that goal. All well and good, but unless someone is shooting very small targets at long range such as prairie dogs at 400 yards, it seems pointless to me.

There aren’t any prairie dogs in Virginia outside of zoos, though we do have groundhogs, which are substantially larger. In practical terms, for my own hunting needs, a centerfire rifle that will put all its shots into 2” at 100 yards is quite adequate. Most of mine will do better than that, though not a whole lot: 1.5 MOA is typical performance and I’m satisfied with it. At 50 yards or so, the difference in POI is maybe a quarter of an inch. The deer don’t notice.

THE GUNS

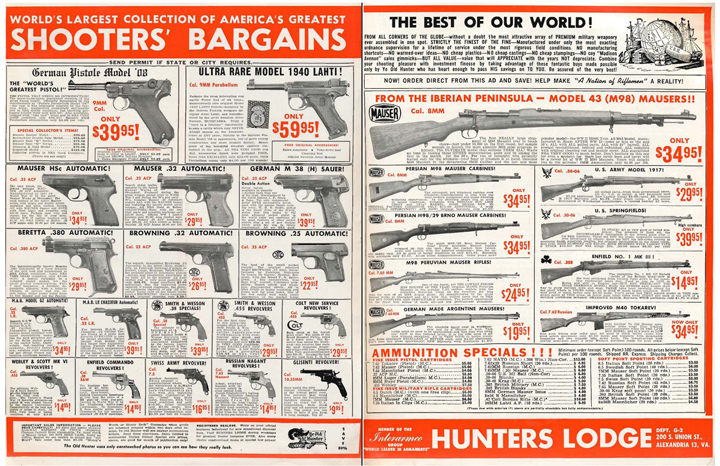

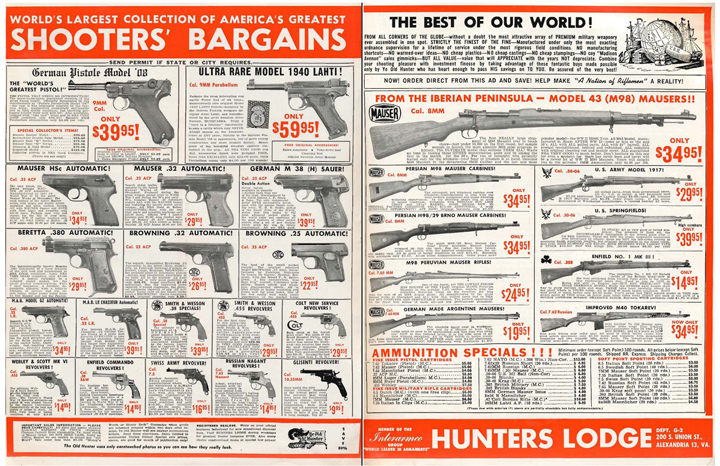

For a large part of my shooting life I only owned surplus military rifles. This was for several reasons: first, they were cheap. In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s shiploads of used military guns came to the USA and sold for prices that make me weep today; if I’d had the money to buy everything that caught my eye in 1963 I’d have retired long before I did!

For a large part of my shooting life I only owned surplus military rifles. This was for several reasons: first, they were cheap. In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s shiploads of used military guns came to the USA and sold for prices that make me weep today; if I’d had the money to buy everything that caught my eye in 1963 I’d have retired long before I did!

My first centerfire rifle was a Carcano carbine identical to the one used by Lee Harvey Oswald which is shown in the famous photo at left. In fact I bought it from the same mail-order house, Klein’s Sporting Goods—in Chicago, of all places—paying $12.88 plus postage. I bought it at age 15, through the mail, and it was delivered to my New York City home along with three boxes of ammunition made by Winchester in 1943. This being before the never-sufficiently-to-be-cursed Gun Control Act of 1968 was passed, it was all perfectly legal. Not long after a neighbor sold me a No. 4 Lee-Enfield sniper rifle for $9. Over the years I “collected” Lee-Enfields, eventually owning many of them, though I have none left. Nor do I still have the Carcano or any of the other military rifles.

The ad above is from a gun magazine in 1963. I had to hunt with a shotgun in New York so a centerfire sporting rifle wasn’t of much interest to me until I moved to Virginia. I bought my first one, a Savage 110, in Virginia perhaps 30 years ago. It’s a .30-06 and likely the best $183 I ever spent on a new gun. Since then I've acquired a Husqvarna Model 640 in 8x57 and a beautiful Kimber 84M in .308. These three mainstays serve 99.9% of my hunting needs for a rifle. The E.R. Shaw .416 was ordered for my once-in-a-lifetime elephant hunt in 2013 and is so specialized it will probably never be used again.

SHOTGUNS

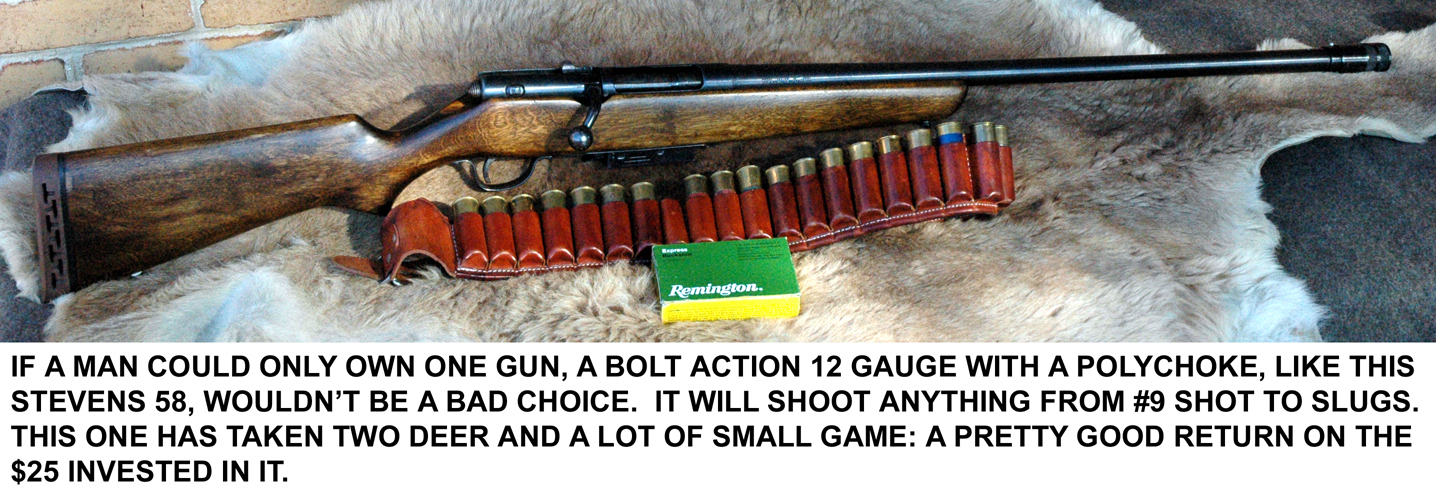

In New York I hunted deer with the Stevens Model 58 bolt action above. It cost me $25. I had bought it, minus the stock, for $10 out of an ad in the base newsletter at Andrews AFB in 1971. $15 got me a new stock from the factory. A real bargain!

I like double shotguns and have owned a few. The “survivors” include a plain-vanilla Stevens 311 in 12 gauge, and a Spanish made double in 20 gauge, plus a couple of Pedersoli muzzle-loading doubles.

My first gun was a shotgun: that single-shot Western Field 20 gauge (really a Stevens Model 94Y bearing Montgomery Ward’s private label) that was in the country house in 1961. I’ve no longer got that one, but I have an identical gun, also by Ward’s, also a 94Y, but labeled “Hercules” instead of "Western Field."

I really like combination guns, especially drillings. My 1940-vintage Burgsmüller drilling (16x16 over 8x57JR) came from Cabela’s “gun library” courtesy of some unknown soldier who brought it home in 1945 as a war souvenir. What a gun! It’s beautifully made and as good as the day it left the factory in Kreiensen seventy-nine years ago. But my pride and joy is a humble little Stevens 24-S in .22 LR over 20 gauge. It's nothing fancy, and sold for about $25 in 1967. It's been heavily modified over the time I’ve owned it into a more or less specialized squirrel-killing machine: I shortened the barrels, had the shotgun barrel fitted with choke tubes, and put a scope on it. I’d undertake to walk across Alaska with this gun.

I really like combination guns, especially drillings. My 1940-vintage Burgsmüller drilling (16x16 over 8x57JR) came from Cabela’s “gun library” courtesy of some unknown soldier who brought it home in 1945 as a war souvenir. What a gun! It’s beautifully made and as good as the day it left the factory in Kreiensen seventy-nine years ago. But my pride and joy is a humble little Stevens 24-S in .22 LR over 20 gauge. It's nothing fancy, and sold for about $25 in 1967. It's been heavily modified over the time I’ve owned it into a more or less specialized squirrel-killing machine: I shortened the barrels, had the shotgun barrel fitted with choke tubes, and put a scope on it. I’d undertake to walk across Alaska with this gun.

MUZZLE-LOADERS

My black powder rifles run the gamut from .32 to .72, for everything from squirrels to big antelope. The .72 is made by Pedersoli, and surely the only double rifle I’ll ever own. Thompson Center no longer makes sidelock guns, damn it; they have succumbed to the in-line craze, though they made the finest production sidelocks in the USA for many years. These so-called “primitive” guns, properly understood and used within their limitations, do the job admirably. I’m one of the few people left in Virginia who hunts with a sidelock rifle; ever since the DGIF allowed in-line muzzle-loaders with scopes for deer hunting (neither was permitted in the early years of the muzzle-loading seasons) nearly everyone has shifted over to a scoped in-line.

My black powder rifles run the gamut from .32 to .72, for everything from squirrels to big antelope. The .72 is made by Pedersoli, and surely the only double rifle I’ll ever own. Thompson Center no longer makes sidelock guns, damn it; they have succumbed to the in-line craze, though they made the finest production sidelocks in the USA for many years. These so-called “primitive” guns, properly understood and used within their limitations, do the job admirably. I’m one of the few people left in Virginia who hunts with a sidelock rifle; ever since the DGIF allowed in-line muzzle-loaders with scopes for deer hunting (neither was permitted in the early years of the muzzle-loading seasons) nearly everyone has shifted over to a scoped in-line.

Because woodland ranges are so short, because the special seasons allow four extra weeks to get into the field, and because Virginia has very generous deer seasons and bag limits, I do a lot of deer hunting with muzzle-loaders. Even though my eyes aren’t what they were when I was in my 30’s and 40’s, I can still use a peep sight at normal woodland ranges. All of the muzzle-loaders are fitted with them. I kill as many (if not more) deer with one of these “primitive” guns as with a modern rifle.The early black powder season starts two weeks before rifle season. I usually kill one or two deer then; there’s also a late black powder season after the rifle season has closed. The early season is best because the deer are still pretty naïve and there are a lot of young-of-the-year who haven’t been “educated” by being shot at and missed. The late black powder season is a tough one. Not only is it cold, all the stupid and unlucky deer are dead; the ones remaining are the hardened and wary survivors.