In 1971 I was in the Air Force and had just returned from an overseas tour. My duty station was a very large base in the Washington DC metropolitan area, and since I’d been a gun collector and shooter for years, I didn’t pass up the opportunity this presented to visit the premises of Potomac Arms, the famous surplus gun house in Alexandria, Virginia. Flush with cash from an “enforced savings program” in my previous posting (where there was nowhere to spend money) and a recent promotion, I decide to buy myself a rifle as a present. Specifically, I wanted a Lee-Enfield No. 1 Mark III.

I’ve always been interested in SMLE’s, though I can’t tell you why. There is just something about Enfields that appeals to me: their simplicity, ruggedness, proven battle record, and long, long service to “King & Country” has something to do with it. There’s also the fact that they’re so homely—there really is no other word that fits—that they have a certain goofy charm of their own, like a moose calf.

I did buy an SMLE at Potomac Arms: one made in Australia at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory in the year 1923. I’d been after a World war One vintage SMLE, but this was as close as they had. With it I bought a Lithgow-made bayonet, dated 1919. Might as well have the full outfit, right? To be honest I didn’t then even know that SMLE’s had been made in Australia, and it was only after nosing around in some reference books that I found out what that seven-pointed star on the butt socket meant.

The SAF was opened in 1912 and produced its first SMLE in 1913. It continued to make SMLE’s long after other factories producing Lee-Enfields had changed over to making No. 4 rifles. The last of 640,000 SMLE’s made in Australia left the factory in 1955, about the same time that the No. 4 production in the UK came to an end. SAF Lithgow also made Bren and Vickers machine guns, and, during the Great Depression, such oddities as sheep clipping shears, golf clubs, toasting forks, and many other civilian gadgets to keep the workers employed.

The rifle I’d bought was in decent shape with a good bore, though obviously it had been used. On one side of the buttstock was scratched the name “BETTY,” which I took to be the name of the girlfriend or wife of a man to whom it had been issued; such “personalization” is common on combat weapons.

The rifle I’d bought was in decent shape with a good bore, though obviously it had been used. On one side of the buttstock was scratched the name “BETTY,” which I took to be the name of the girlfriend or wife of a man to whom it had been issued; such “personalization” is common on combat weapons.

Interestingly, it’s marked “No. 1 Mark III*”. Rifles thus marked that were made in the UK lack a magazine cut-off and the slot for it. These manufacturing steps were eliminated as an economy measure after 1916, accounting for the “*” to indicate a minor modification. Despite its marking, this one does have the cut-off, and is really in “Mark III” configuration. I shot it a few times, and then put it away for years, another rack queen in a growing collection of Enfield rifles.

Interestingly, it’s marked “No. 1 Mark III*”. Rifles thus marked that were made in the UK lack a magazine cut-off and the slot for it. These manufacturing steps were eliminated as an economy measure after 1916, accounting for the “*” to indicate a minor modification. Despite its marking, this one does have the cut-off, and is really in “Mark III” configuration. I shot it a few times, and then put it away for years, another rack queen in a growing collection of Enfield rifles.

In 1985, I wrote to the SAF in Lithgow to ask if they had any records on the gun. Beyond what I already knew they couldn’t add much: only that the rifle was transferred from their custody to the Australian Department of Defence, and that it almost certainly had been used in World War Two. But there was no record of its issuance to any individual. The Australian Department of Defence never replied to inquiries. That was that, I forgot about it.

Until 23 years later, when out of the blue I received a letter from Mr John Wray, Secretary/Custodian of the Lithgow Small Arms Factory Museum, that read:

The Museum was formed in 1996 when the SAF collection was handed over to the people of Lithgow. It operates as a not-for-profit organisation…When sorting through the Museum’s archives last week, one of our volunteers came across a letter written by yourself in 1985 seeking information…The reason for this letter is to find out if you still own this rifle, and if so, are you willing to part with it?

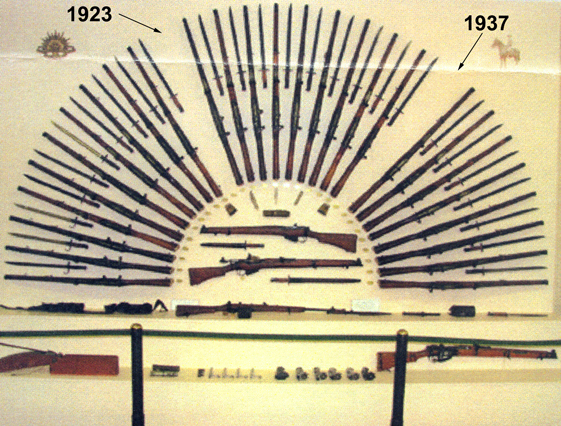

Last year a Queensland handgun collector donated his entire…collection to the Museum. In March this year the Museum opened a new exhibition room to house this collection. The centerpiece display in this room is a display of Lithgow SMLE’s from every year of manufacture. 1923 and 1937 are missing and we are hoping that we can find one of each to complete the display.

I didn’t have to think very long or hard about the request: having reached an age where I’m thinning out my collection, where better to send one of my guns than to a museum, where it would be safe from confiscation and an end in smelter? Moreover, not just any museum, but one where it was actually made? I replied to Mr Wray by e-mail that the rifle was theirs as soon as I could get it to them, that I was happy to donate it, and that I was flabbergasted that they had managed to track me down to my correct address after more than two decades and a move to another state. If they wanted it enough to go to that much trouble to find me, they were welcome to it!

I didn’t have to think very long or hard about the request: having reached an age where I’m thinning out my collection, where better to send one of my guns than to a museum, where it would be safe from confiscation and an end in smelter? Moreover, not just any museum, but one where it was actually made? I replied to Mr Wray by e-mail that the rifle was theirs as soon as I could get it to them, that I was happy to donate it, and that I was flabbergasted that they had managed to track me down to my correct address after more than two decades and a move to another state. If they wanted it enough to go to that much trouble to find me, they were welcome to it!

Then I started making inquiries about how to ship it. This is a good deal more complicated than one might think. I found out that you can’t just pack a rifle up and mail it. Oh, no, there are several US government agencies involved, but curiously, the BATF isn’t one of them. BATF regulate imports: but exports have to be licensed through the Department of Commerce and/or the State Department.

Why State? Because even though it’s 85 years old and hopelessly obsolete as a serious combat weapon, my SMLE was nevertheless on the “Munitions List,” of “Implements of War” that required special permission for export. Well, OK, I can see the point: after all, Afghan mujaheddin were using SMLE’s to kill Russians in the 1980’s! We wouldn’t want this dangerous weapon to fall into the wrong hands, now would we?

Why State? Because even though it’s 85 years old and hopelessly obsolete as a serious combat weapon, my SMLE was nevertheless on the “Munitions List,” of “Implements of War” that required special permission for export. Well, OK, I can see the point: after all, Afghan mujaheddin were using SMLE’s to kill Russians in the 1980’s! We wouldn’t want this dangerous weapon to fall into the wrong hands, now would we?

The rules pertaining to export are so numerous, the required permits and clearances so complicated, and the paperwork so voluminous, that it’s much easier to bring a rifle into the USA than it is to send one out. BATF only requires a Form 6, but State's rules are Byzantine. I needed someone with an export license and expertise who could handle the job, and there I ran into a snag.

Because the preparation of a shipment is so time consuming, most companies with licenses to export don’t want to handle a one-off situation like this. Several told me, “We ship commercial lots of 50 or more rifles, we can’t do just one.” I next turned to several collector’s auction houses, well-known companies who routinely ship to foreign countries, only to be told, “We only ship things we’ve sold in our auctions; and that rifle isn’t worth enough to bother with, anyway.” It took me a week of e-mails and phone calls to find someone with the proper license who was willing to do the job: High Bridge Arms, which also happens to be the last surviving gun store in San Francisco. Their export department, run by Ms Lauren Takahashi-Toffolo, was extremely helpful, and said, “Sure, we can handle it; we ship to Australia all the time. All I need is an order from the Museum and a copy of the importation paperwork from their end.” They made it so easy that I would highly recommend anyone who has a reason to export a firearm to contact High Bridge and ask them for assistance.

My end was set up: the ball was now in the Museum’s court. Mr Wray having been taken ill, I was contacted by a Ms Donna White, also of the Museum staff, who explained that they have a special status under Australian firearms law. She had applied for a “B709A” import permit. That arrived shortly afterwards and a copy was faxed to High Bridge. The export permit arrived in record time—Lauren said someone in DC must have been “working overtime”—so all I had to do was box the rifle up and send it via US Postal service to California. From there it crossed the Pacific by International Priority Mail.

My end was set up: the ball was now in the Museum’s court. Mr Wray having been taken ill, I was contacted by a Ms Donna White, also of the Museum staff, who explained that they have a special status under Australian firearms law. She had applied for a “B709A” import permit. That arrived shortly afterwards and a copy was faxed to High Bridge. The export permit arrived in record time—Lauren said someone in DC must have been “working overtime”—so all I had to do was box the rifle up and send it via US Postal service to California. From there it crossed the Pacific by International Priority Mail.

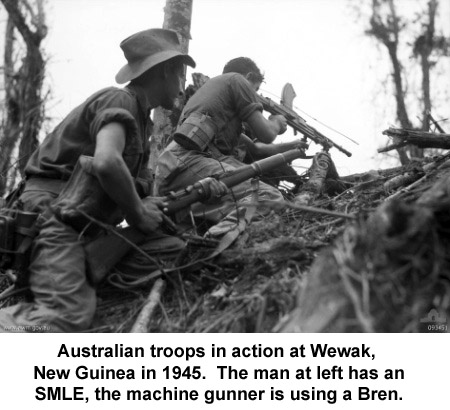

I have no way of knowing where this rifle has been, who carried it, or whether and when it was used “in anger.” It may have stood guard at Australian Army Headquarters in Canberra, or it may have been in the thick of things at Tobruk or Wewak. The old cliché, “If only it could talk!” certainly applies here: the men who designed and built it, and probably those who used it, are dead and gone, but it will stand as their mute memorial on a wall in Lithgow.

Maybe, just maybe, “Betty” will see it someday and remember the man who carved her name on a weapon as a talisman and an expression of his hope of returning to her. In 85 years it has traveled far and wide, but now it’s on its way into honored retirement.

POSTSCRIPT, APRIL 24, 2012

The rifle fan is complete! I received this e-mail from the Museum on April 19th:

It is my great pleasure to send you an email to let you know that the Museum now has the 1937 SMLE rifle and has completed the "rising sun" display. A New Zealand collector knew of another collector over there who owned one. He bought it from him and donated it to our museum. It is ironic that both the missing rifles, your 1923 and the 1937, came from other countries! Our guides like to tell the story of how we came about these two rifles to our visitors.

We very much appreciate your efforts as well as those of the other collectors who kept their eyes out for us. I have attached a photo of the completed display.

The Centenary of the Lithgow Small Arms Factory falls in June this year, and it is great to have the display completed in time for our own celebrations of the Centenary in October (to get away from our cold Lithgow winter).

We all hope you may be able to visit the museum one day.

Kind regards,

Donna White, Custodian

And here it is:

Read the article about it in the Lithgow Mercury

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |