Lupines are a common sight along the roads in Maine in early June

We’ve returned from another marathon-drive vacation, this time to the Rock-Bound Coast Of Maine and Cape Cod. We’ve been to the Pine Tree state several times, beginning in 1975 on our honeymoon.

We then stayed at "The Harborage," a bed-and-breakfast in Boothbay Harbor that we liked; and did it again 20-odd years later when it was run by the grandchildren of the people who’d owned it in 1975. Now as we close in on 43 years of marriage, we stayed for the third time. After some extensive touring in other parts of Maine we returned after a couple of days at Cape Cod where some old friends own a cottage.

We flew from Richmond to Boston and there rented a car. Roanoke is really the nearest airport to us, but as it seems to be on the every edge of the Airline Universe, flying from Roanoke always requires a stop and an additional $200-250 per ticket. The drive to Richmond took a little over four hours which, while it saved us the excessive additional airfare cost from Roanoke, meant we spent the night in a hotel to catch a very early flight the next day: so the savings weren’t all that great. Charlotte NC is an hour closer to us than Virginia’s capital (there is some sort of lesson there, but I’m not sure what it is) so if we fly again we’d go through that hub.

We flew into Logan Airport in Boston…NEVER AGAIN. Logan isn’t too bad as airports go—JFK is far worse—but Boston is a driver’s worst nightmare come true. I grew up and learned to drive in New York City; I lived 11 years in Washington DC. I can handle heavy traffic; but the chaos in Boston is worse than anywhere I’ve ever seen in the USA, very nearly as bad as Cairo or New Delhi. At intersections Bostonians regard a red light as a mild suggestion to slow down to 45 MPH as they pass through. Boston drivers believe that they have Divine Right Of Way and God help you if you issue a challenge by using a turn signal. A turn signal is like a red rag to a bull: hit one for a lane change and immediately someone will rush up to cut you off. Neither of course do Bostonians use turn signals themselves: half the drivers coming towards you on a surface street can be counted on to turn left right in front of you with no warning, daring you to T-bone them. If you slam on your brakes to avoid doing that you not only reveal yourself as a wussie, you run a very real risk of being rear-ended.

Alas, our GPS directed us onto the main highway northbound only after several miles on Lowell Avenue, perhaps the worst surface street in the USA on which to drive. Fifth Avenue in Manhattan is easier to negotiate, in part because unlike Lowell Avenue, it isn’t being ripped up every 500 feet with the right lane blocked by construction equipment; and it isn’t populated by maniacs. Yet…I learned a beautiful lesson on Lowell Street: that Nature has a certain resilience. As we threaded our way along a semi-industrial stretch, dodging cars and suicidal pedestrians, out of the conglomeration of warehouses, oil storage facilities, barber shops, tattoo parlors, etc. there darted…a rabbit! He pelted headlong across the street and vanished before even the most alert Bostonian could have run him over.

Somehow we survived the free-for-all long enough to get to the main highway to head northeast. At that point it was merely bumper-to-bumper at 50-55 MPH half way to the New Hampshire/Maine state line. It was not unlike driving in one of those Dodge-‘Em car rides at Coney Island. As we entered NH we were intrigued by signs advertising NH’s state-run liquor stores in highway rest stops.

Somehow we survived the free-for-all long enough to get to the main highway to head northeast. At that point it was merely bumper-to-bumper at 50-55 MPH half way to the New Hampshire/Maine state line. It was not unlike driving in one of those Dodge-‘Em car rides at Coney Island. As we entered NH we were intrigued by signs advertising NH’s state-run liquor stores in highway rest stops.

But hey, NH’s motto is “Live Free or Die,” so what else could we expect? There are only perhaps 15 miles of NH Interstate, which gives you barely enough time to get drunk, anyway; so if you manage to do so it’s either Maine’s or Massachusetts’ problem. The very savvy Granite state wants all southbound drivers to know that if they don’t “fuel up” before they hit Massachusetts, they’ll get socked good and hard with outrageous booze prices and sales tax. And to point out that a short northbound trip from Boston will get you the same deal. Get it while you can, folks.

Still completely sober we passed into Maine, turning off I-95 at Freeport to make the absolutely obligatory pilgrimage to the colossal L.L. Bean “campus”. When we first visited Bean’s in 1975 it was in a single frame house not much larger than the one I live in. There was not much else in Freeport except the building where Bean’s actually made their famous boots. Today Freeport is a sprawling semi-urban shopping district with Bean’s as the centerpiece, a multi-building emporium stuffed to the gills with nylon backpacks, skis, canoes, trendy clothes, tents, camping equipment, and dog gear.

After Freeport we headed for Boothbay Harbor on US Highway 1 to “our” B&B, “The Harborage.” I have no memory of how we first found this place. Between our first and second visits the owners had added a deck and some more rooms, but we stayed in one of the original rooms that were there forty-odd years ago.

It sits on a lovely spot looking over the harbor with a pleasant deck on which breakfast is served. I’m no fan of B&B’s but I will say that as such places go The Harborage is quite a nice one. Boothbay Harbor itself is a very pretty tourist town, and luckily we were there before the headlong rush of The Season began.

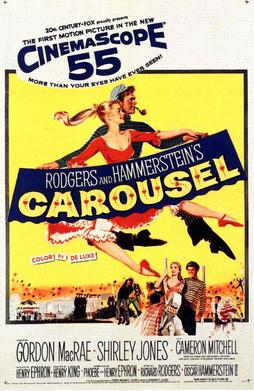

I like beach towns and small working villages. Alas Boothbay Harbor isn’t either one, at least not in the same sense as those phrases are usually meant. Sure, people do work there running B&B’s, popcorn stores, tchotchke shops, and restaurants; but the atmosphere is that of a touristy “destination” and nothing else. If you’ve ever seen the movie Carousel you’ve seen Boothbay Harbor: that’s where it was filmed. Needless to say the people who actually live in Boothbay Harbor (about 1200) are far outnumbered by tourists even in the “pre-season”. Boothbay Harbor is pretty but somewhat…well, artificial. Not quite Disneyland cute, but close.

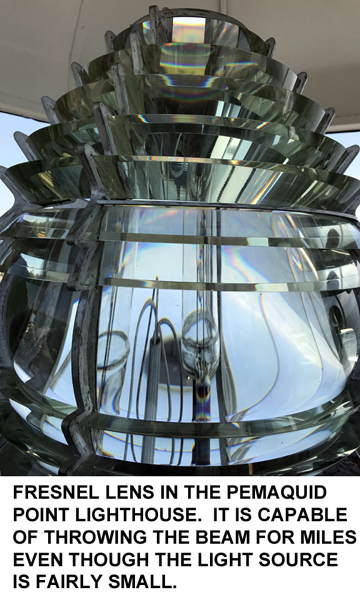

But Boothbay Harbor isn’t the only part of Maine worth seeing. We made a short trip to Pemaquid Point to see the famous lighthouse, one of many along the coast. One would think that in these days of GPS service lighthouses would be obsolete, but not so: all of the lighthouses along The Rockbound Coast Of Maine are still in service, and a good thing, too: some of those rocks are pretty big and running a vessel into them at night would not make the Captain happy. While in The Good Old Days each lighthouse had a keeper, who lived on the grounds and maintained the lamp, today they're pretty much all automated. The picture gives an idea of the size of the tower, which isn't very high (not, as the docent told us, "Anything like as high as the ones on the Carolina coasts") and the light chamber, which is surprisingly small. The special Fresnel lens fills most of the chamber: there's barely room for a person to walk around the lens.

But Boothbay Harbor isn’t the only part of Maine worth seeing. We made a short trip to Pemaquid Point to see the famous lighthouse, one of many along the coast. One would think that in these days of GPS service lighthouses would be obsolete, but not so: all of the lighthouses along The Rockbound Coast Of Maine are still in service, and a good thing, too: some of those rocks are pretty big and running a vessel into them at night would not make the Captain happy. While in The Good Old Days each lighthouse had a keeper, who lived on the grounds and maintained the lamp, today they're pretty much all automated. The picture gives an idea of the size of the tower, which isn't very high (not, as the docent told us, "Anything like as high as the ones on the Carolina coasts") and the light chamber, which is surprisingly small. The special Fresnel lens fills most of the chamber: there's barely room for a person to walk around the lens.

I’d never been up in a lighthouse, but we were allowed to go up into this one; I was amazed at how cramped the light chamber is and how steep and dangerous are the winding stairs leading up to it. We went up and down safely but someone in a wheelchair…well, tough luck, there’s no elevator!

I’d never been up in a lighthouse, but we were allowed to go up into this one; I was amazed at how cramped the light chamber is and how steep and dangerous are the winding stairs leading up to it. We went up and down safely but someone in a wheelchair…well, tough luck, there’s no elevator!

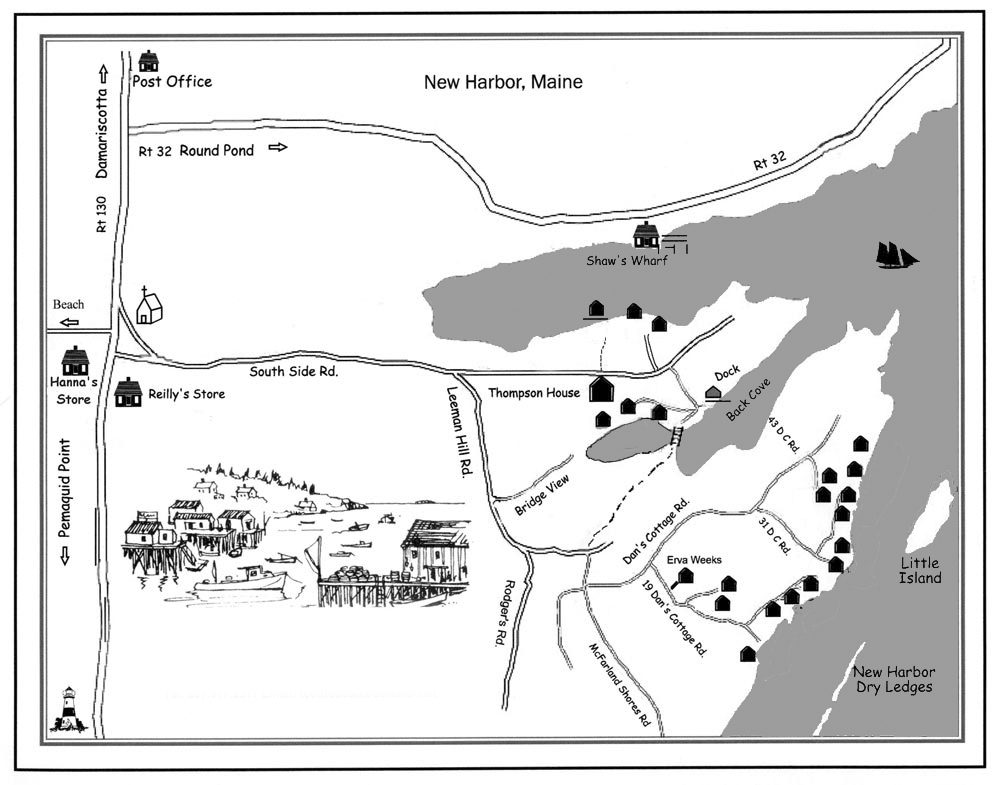

On the way back from Pemaquid Point we stopped to look at some housekeeping cottages in New Harbor, a place much more in keeping with my ideals. New Harbor is a very small (population 745) working fishing village on the Pemaquid Peninsula and it’s not an imitation village. New Harbor has a few houses, two small general stores, a church and the cottages. That’s pretty much it. The cottages are lovely, very scenic, spotlessly clean and totally without TV or Internet service; even cell phones don’t work in them. There is nothing to do, as the owner proudly noted. “People come here to relax! Not to watch TV!” And I must say that the prospect of a week with nothing to do but sleep, eat, read and fish has a very strong appeal. Plus the cottages come with rowboats. What’s not to like?

On this map you see pretty much the entire layout of New Harbor, with the cottages indicated. "Shaw's Wharf" is the place where the day's catch of lobsters is landed.

In the image above of New Harbor's working area the lobster wharf is in the right foreground. Proof that New Harbor is a real place and not a tourist destination is the price of lobster. In Boothbay Harbor a boiled lobster will set you back $35-50; in Bar Harbor not much less. But in New Harbor the lobster wharf sold me TWO lobsters, fresh out of the water, for $19. Since one major reason I went to Maine in the first place was to eat lobster I was delighted that they’re that affordable in a lovely quiet setting.

Then it was Ho! For Mount Desert Island, Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, again via US Highway 1. We made a lunch stop in Camden, another tourist town rather larger than Boothbay Harbor, and consequently having a greater number of overpriced restaurants. It’s also much less “walkable” than tiny Boothbay Harbor; but we had a stroke of luck and found a parking space on the main street. The last time we went through Camden we’d done a ride in a lobster boat with a group of seasick Boy Scouts, but we passed up another chance this trip. We needed to get to Bar Harbor.

Bar Harbor is the principal town on Mount Desert Island. If anything it’s even more touristy than Boothbay Harbor or Camden, but to make up for that it’s also even more picturesque. It was once the “in” place for rich people to “summer,” among them the Rockefellers, a few of whom still have houses there. The town gets its name from a sandbar that’s exposed at low tide allowing one to walk across to Bar Island, perhaps 300 yards from Mount Desert Island.

We did this, it’s more or less a mandatory thing for tourists to do. Sometimes people get “trapped” on Bar Island if they forget about the tides: and not a few seem to be stupid enough to drive onto and park cars on the sandbar, only to watch them become inundated with seawater when the tide comes in. Filling a car with salt water doesn’t improve its performance; filling a rental car with seawater would be an expensive mistake.

The larger harbor looking out on Frenchman Bay is quite beautiful. From it we took a brief cruise on the Bay aboard a sailing ship, Margaret Todd. Though she looks like a windjammer from before World War One, in truth she’s a reproduction only 20 years old.

That two-hour cruise was one of the high points of the trip, largely because there were 30-40 Newfoundland Retriever dogs on board (as well as one Golden Retriever puppy I’d have bought on the spot). A Newfie owners’ club had booked the vessel for a sail. Since we’re dog people we had no objection to the presence of so many big hairy canines, and in fact had a nice time playing with them and chatting with the owners. There were a couple of small children on board as well, and I have to say the dogs were much better behaved than the kids were.

That two-hour cruise was one of the high points of the trip, largely because there were 30-40 Newfoundland Retriever dogs on board (as well as one Golden Retriever puppy I’d have bought on the spot). A Newfie owners’ club had booked the vessel for a sail. Since we’re dog people we had no objection to the presence of so many big hairy canines, and in fact had a nice time playing with them and chatting with the owners. There were a couple of small children on board as well, and I have to say the dogs were much better behaved than the kids were.

Not just Margaret Todd is dog friendly, so is all of Bar Harbor. Dogs were everywhere and all the businesses put out water bowls for them. “No Dogs Allowed” signs were very rare. Most businesses seemed to welcome dogs, some even posting signs indicating “Dogs Welcome.” There were dogs all over the town; I’d estimate the tourist: dog ratio was about 2:1 and that may be too low. Dogs were even present in one or two restaurants.

Bar Harbor’s biggest draw (besides the scenery) is Acadia National Park (where the biggest draw is the scenery). Acadia is one of the smallest NP’s, and sits on land donated by rich people, among them the Rockefellers, who seem to be as numerous in Bar Harbor and environs as black flies in the Summer. Acadia has breathtaking sea views from a perimeter road. You can drive to reach them, I’m happy to say. There are many hiking trails, but neither of us are hikers.

Another feature of Acadia is a network of carriage roads. These were built by—who else?—the Rockefeller family. These carriage roads have numerous stone bridges over streams and existing automobile roads, each bridge somewhat different and each one expressing the creative whim of whichever architect was hired by the Rockefellers to design it. Needless to say we signed on for a carriage ride.

Our driver and guide was an Amish gentleman hired for the Summer, presumably because he knew how to drive a horse-drawn carriage, a skill set not easily found in today’s world. The carriage was drawn by a team of two  big Percheron mares, “Betty” and “Reba.” I assume that Reba was named for the country music star and would hazard a guess that Betty was named after…Betty Grable? Betty Ford? Given the size of her butt, could it have been Bette Midler? Who knows? They plodded us along quite nicely, stopping when told to do so in order for us to admire the stonework on some bridge or another. Note the 1917 date on the bridge in the picture above. Our guide pointed out that Mr Rockefeller had “…kept 150 men employed all through two world wars and the Depression,” which no doubt gladdened the hearts of those men who were thereby excused from the military draft to do the “essential war work” of constructing tourist roads and bridges, though it might have pissed off the ones who were sent to the trenches in their places.

big Percheron mares, “Betty” and “Reba.” I assume that Reba was named for the country music star and would hazard a guess that Betty was named after…Betty Grable? Betty Ford? Given the size of her butt, could it have been Bette Midler? Who knows? They plodded us along quite nicely, stopping when told to do so in order for us to admire the stonework on some bridge or another. Note the 1917 date on the bridge in the picture above. Our guide pointed out that Mr Rockefeller had “…kept 150 men employed all through two world wars and the Depression,” which no doubt gladdened the hearts of those men who were thereby excused from the military draft to do the “essential war work” of constructing tourist roads and bridges, though it might have pissed off the ones who were sent to the trenches in their places.

That ride made me realize how long it must have taken people to get anywhere before the invention of the “horseless carriage” and how uncomfortable it must have been. Now, we were on properly maintained, properly graded, properly graveled roads, bouncing along at a pace a walking man could match. (And a good thing, too: if Betty and Reba had moved any faster we’d have been thrown out of the carriage.) The pioneers who crossed The Great Plains had to do it without the benefit of any roads, and their wagons were drawn by oxen, not trained Percherons. Once roads of a sort had been made it would have been faster to travel in a horse-drawn Wells Fargo stagecoach but that must have been pure torture, even worse than a coach class airline seat. A stagecoach might have made 20 miles in a day under ideal conditions; a pioneer wagon train would be lucky to do half that. Furthermore today we don’t have worry about being scalped by hostile Indians or held up by the James-Younger Gang. Let us all be grateful for rubber tires, gasoline engines, hard-paved roads and most especially the Interstate highways.

We’ve been to quite a few National Parks. Although the Park System stresses the “natural beauty” and “wildness” of their properties, in truth they aren’t really very wild. The National Parks are “Nature” that’s been tamed, shackled, and made subservient to the needs of tourists. While there are certainly exceptions (e.g., much of Denali NP) for the most part in the National Parks everything is controlled and civilized and no one seriously expects any major inconveniences. The parks have good roads, proper toilets, restaurants, telephone service and Visitor Centers. If somehow you get hurt an ambulance crew can get to you. Truly “wild” animals (again, with some exceptions) aren’t permitted to interfere with the tourists’ belief that they’re experiencing “Nature” as it really is. I’ve hunted deer in Virginia woodlots that are wilder than anything we saw in Acadia. In fact of wildlife we saw none beyond a wild turkey on the berm of Interstate 95 and another wandering around near the streets of Bar Harbor. It seems to me that any place that’s really “natural” ought to have a coyote or two and perhaps a few birds, but if such exist in Acadia NP (as we were assured they did) there was no evidence of it.

Having done with Acadia we pushed on. It seemed reasonable, since we were pretty far up the coast, to go on to see Campobello Island, where Franklin Roosevelt had a summer home. This is actually in Canada; we traversed a very small bridge and stopped at the Canadian border crossing kiosk where we were asked by a border guard whether we had any firearms, drugs, “weapons” (whatever that means: does my pocketknife count?) and so forth; she cleverly spotted the bar-coded decal on the car window and asked if the car was rented; didn’t inspect anything, asked why we were visiting and how long we expected to be in Canada. After we told her maybe two hours (it wasn’t even that long) she smiled and welcomed us and that was that.

I always have a hard time thinking of Canada as a foreign country. When you cross into Mexico things are different and the differences are apparent. But Canada looks exactly like the USA, people sound like Americans, and except for “poutine” (a local delicacy consisting of French fries with cheese curds and gravy that is probably as nauseating as it sounds) the food is the same. Everyone there takes credit cards from American banks and US currency is widely accepted (at an unfavorable rate) in local shops.

The Roosevelt “cottage” on Campobello Island is a modest 40-room, 6-bath wood frame house, which isn’t at all grand by the standards of the time it was built. It’s now owned and maintained by a foundation as a bi-national historic site. FDR’s domineering mother, Sarah Delano Roosevelt, had it built and given to Franklin and Eleanor as a gift. (FDR’s mother was a piece of work; why Eleanor didn’t shove her virago of a mother-in-law into the Bay of Fundy when they were out sailing one summer is beyond me. “Whoops, Franklin, Mama has fallen overboard! And oh, dear, the wind is shifting, taking us back to shore….”) Most of the objects and furniture in the house are original to it, and give a pretty good picture of the life of a family wealthy enough to have a “cottage” that size and to bring along their servants when they “summered” there. It isn’t up to the standards of the opulent excesses of the Robber Barons of Newport RI to be sure, but ‘tis enough, ‘twill serve.

Coming back into the USA we were again questioned, this time by an American border guard who wanted to know how long we’d been gone, was that a rental car, did we have the rental agreement (we did but couldn’t find it) and would I please open the trunk? Satisfied that a) we weren’t smuggling drugs in from Campobello Island and b) that he had had enough excitement for one day, he waved us on and we were once again in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave.

We had been advised to see Eastport, another Maine coastal town not too far from Campobello, so off we went. Eastport is pleasant enough but it’s trying desperately to be another Boothbay Harbor, despite really being very far off the beaten track. I hope they achieve their goal but the town’s biggest claim to fame seems to be a huge statute of a fisherman right down on the harbor seawall. This statue was actually made for a TV movie shot there about 15 years ago, and the town coughed up the funds to keep it in shape, I assume with the thought that it would be a big “draw”. Maybe it is. We were there in the “pre-season” so I don’t know how heavy their tourist trade may be in the high season. I did have a pretty decent cup of coffee in one of the harbor side places that seemed to specialize in cupcakes. One thing about Eastport is that unlike Boothbay Harbor, it’s an actual working port; boats were loading lobster traps down on the long quay. Having had our fill of the one street in Eastport we headed back west to go to Cape Cod and our friends’ home. This entailed a long, long drive across central Maine via State Route 9, as far as Bangor, where we could get on I-95.

We had been advised to see Eastport, another Maine coastal town not too far from Campobello, so off we went. Eastport is pleasant enough but it’s trying desperately to be another Boothbay Harbor, despite really being very far off the beaten track. I hope they achieve their goal but the town’s biggest claim to fame seems to be a huge statute of a fisherman right down on the harbor seawall. This statue was actually made for a TV movie shot there about 15 years ago, and the town coughed up the funds to keep it in shape, I assume with the thought that it would be a big “draw”. Maybe it is. We were there in the “pre-season” so I don’t know how heavy their tourist trade may be in the high season. I did have a pretty decent cup of coffee in one of the harbor side places that seemed to specialize in cupcakes. One thing about Eastport is that unlike Boothbay Harbor, it’s an actual working port; boats were loading lobster traps down on the long quay. Having had our fill of the one street in Eastport we headed back west to go to Cape Cod and our friends’ home. This entailed a long, long drive across central Maine via State Route 9, as far as Bangor, where we could get on I-95.

There’s an old saying that “There are three seasons in Maine: Winter, Mud, and Road Construction.” We were there in Road Construction. The secondary roads were torn up in many places for repair after the ravages of the long and brutal Winter. When I say “torn up,” I don’t mean the sort of thing we see in Virginia when potholes are being patched. There were miles-long stretches of US 1 and State Route 9 that simply had no pavement at all, it having been removed by the repair crews and its replacement not yet laid down. “Pavement Ends” signs popped up periodically and then we were in for 3-5 miles on dirt and gravel (the latter if there had been some temporary patching done). The Interstate was fine once we got there, but the secondary and tertiary roads get a terrible beating from winter frost heaves. This slowed us down somewhat but given that there was little traffic, it was OK. Lowell Street in Boston was worse, if shorter.

There’s an old saying that “There are three seasons in Maine: Winter, Mud, and Road Construction.” We were there in Road Construction. The secondary roads were torn up in many places for repair after the ravages of the long and brutal Winter. When I say “torn up,” I don’t mean the sort of thing we see in Virginia when potholes are being patched. There were miles-long stretches of US 1 and State Route 9 that simply had no pavement at all, it having been removed by the repair crews and its replacement not yet laid down. “Pavement Ends” signs popped up periodically and then we were in for 3-5 miles on dirt and gravel (the latter if there had been some temporary patching done). The Interstate was fine once we got there, but the secondary and tertiary roads get a terrible beating from winter frost heaves. This slowed us down somewhat but given that there was little traffic, it was OK. Lowell Street in Boston was worse, if shorter.

I had insisted we stop in Kittery (the first town in Maine after you leave NH) on the way to Cape Cod. I wanted to meet a friend at the famous Kittery Trading Post. KTP is the grandfather all outdoors mega-stores, quite literally. It was opened in 1938 and between them KTP and the now-long-gone-and-much-lamented original Herter’s they could supply anything at all an outdoorsman might need. My friend Ralph lives nearby, frequently goes to KTP “..to see what they have” and met us there. We shooed my wife off to shop in the innumerable factory outlets nearby (Kittery has gone all Freeport on us since I was first there in 1972) while Ralph and I toured the place. KTP has virtually everything an outdoorsman could imagine.

There were indeed wonderful things there: had I not been in the stage of life when I’m “thinning the herd” I’d have succumbed to the siren songs of miscellaneous classy doubles and drillings. If I had to choose between blowing a lot of money at KTP or in a Las Vegas casino, KTP would win every time. But I manfully resisted temptation—as I do in Vegas, I hasten to say—and after a couple of hours we were back on the Interstate headed for Cape Cod via Salem and Plymouth. Regrettably the route lay through the Boston suburbs, because we were going to Salem, which had several attractions. The Peabody-Essex Museum for one; and the “House of Seven Gables” for another. Alas the road to Salem involved another drive on Lowell Street with all its pitfalls, potholes, and lunatic drivers.

We made it to the PEM, 2-1/2 hours before it closed. And they would simply not budge on the extortionate price of admission: $24 EACH for Geezer Tickets, take it or leave it, if you don’t like it, go see some other museum. Oh, and that price didn’t include “Yin Yu Tang,” the Chinese House exhibit, that will be another $6 EACH, please. The Chinese House was built 200+ years ago as the home for a prosperous businessman and his extended family. It was dismantled and brought, piece by piece—including the outer courtyard with its stuccoed wall—to the PEM and re-assembled. Needless to say, this stupendously expensive undertaking was paid for by grant monies: your tax dollars at work.

We made it to the PEM, 2-1/2 hours before it closed. And they would simply not budge on the extortionate price of admission: $24 EACH for Geezer Tickets, take it or leave it, if you don’t like it, go see some other museum. Oh, and that price didn’t include “Yin Yu Tang,” the Chinese House exhibit, that will be another $6 EACH, please. The Chinese House was built 200+ years ago as the home for a prosperous businessman and his extended family. It was dismantled and brought, piece by piece—including the outer courtyard with its stuccoed wall—to the PEM and re-assembled. Needless to say, this stupendously expensive undertaking was paid for by grant monies: your tax dollars at work.

I suppose that 200 years ago in China, the Huang family that owned this house lived pretty well compared to the average peasant. They had numerous rooms, all of them small and stuffy; and there were small ponds in the courtyard to hold the unfortunate fish who would eventually become dinner. There were chamber pots in all the living spaces. The children of the family dutifully went around each day to collect the—ahem—night soil, which was then dumped on the garden plot where the vegetables were grown, thus fertilizing it and simultaneously adding to the large numbers of parasite eggs and cysts that were then ingested with the vegetables (and the fish), thus completing their life cycle with humans as intermediate hosts.

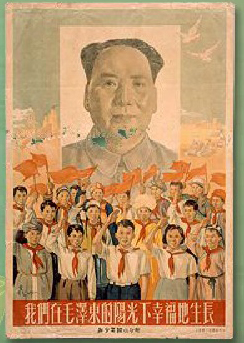

The main room contained numerous artifacts including a sort of tapered barrel, which turned out to be a version of a child’s high chair. The infant was placed in it; he could not climb out; and he was thus secured from injury or any real need for supervision. During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s, the Huangs, being rich people, were openly denounced as Enemies of the State by the Communist government. Two of their bedrooms were “confiscated” and in them were housed two families of the local peasantry. The senior Huang was thereby declared and denounced as the worst thing in the Chinese Communist lexicon: a “landlord,” though it’s a certainty that he received no “rent” from the people forced on him at gunpoint.

Possibly as a safeguard against further oppression, and a minimalist form of protection from being shot as “bourgeois anti-Revolutionaries” the portraits of the Huang ancestors were removed and replaced with pictures of The Great Helmsman, Chairman Mao. Mao’s visage beamed down upon the happy Huang family where they ate and slept; and to be certain they didn’t forget who was in charge, in addition to the men with the rifles out in the street, a loudspeaker was placed in the main room; this loudspeaker blared “patriotic” songs and propaganda, not to mention orders and accounts of the wonderfulness of The Great Helmsman, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. To be sure that the message got across, the loudspeaker could not be turned off and it could not be removed. Just like CNN in a modern-day airport waiting area, but at least in most airports you don’t get shot if you try to escape the harangue.

All in all, however, I think the $12 extra fee was worth it to see how a well-to-do family of China from 200 years ago lived: and the conclusion is that by modern day standards they lived in what a polite person would call “squalor”. No privacy, stinking chamber pots, mosquito breeding pools in the front yard, no heat in winter, nor cooling in summer; beds only for the master and mistress of the house (after 1965, that would be the “landlord” and his wife) and any number of strangers to be fed and housed under compulsion. Quite a life. But all must share the burden, or else.

All in all, however, I think the $12 extra fee was worth it to see how a well-to-do family of China from 200 years ago lived: and the conclusion is that by modern day standards they lived in what a polite person would call “squalor”. No privacy, stinking chamber pots, mosquito breeding pools in the front yard, no heat in winter, nor cooling in summer; beds only for the master and mistress of the house (after 1965, that would be the “landlord” and his wife) and any number of strangers to be fed and housed under compulsion. Quite a life. But all must share the burden, or else.

Even though we’d paid a huge admission charge, and there was hardly anyone else in the museum, we were chivvied through the Chinese house by an officious jackanapes of a guard who hustled us out before we had had a chance to see it all. We complained to the lady at the ticket desk and she then led us back into the place by the exit: this did not please the guard who again tried to throw us out “to make room for the next group,” despite the facts that a) there was no group behind us; and b) the PEM was closing in half an hour anyway.

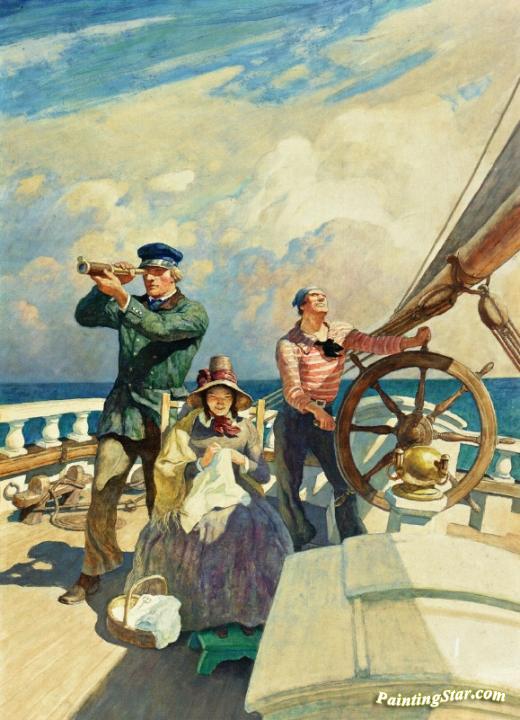

There were some things in the PEM worth seeing. One was the original of an N.C. Wyeth painting, They Took Their Wives With Them, a beautiful image of a Maine sea captain’s spouse placidly knitting on the deck of her husband’s ship as it sailed along. This picture was done for Kenneth Roberts’ book Trending Into Maine, and I spotted it as a Wyeth first thing as we entered. I am a fan of both Roberts’ work and N.C. Wyeth’s, whose style is unmistakable. Roberts was the finest historical novelist the 20th Century produced, and N.C. Wyeth its greatest illustrator and artist. Putting Wyeth’s work into Roberts’ book was inspired. I have a copy of the first edition of Trending Into Maine and was tickled to see this rather small piece “in person” because the reproductions don’t really do justice to the brilliance and vividness of Wyeth’s images.

There were some things in the PEM worth seeing. One was the original of an N.C. Wyeth painting, They Took Their Wives With Them, a beautiful image of a Maine sea captain’s spouse placidly knitting on the deck of her husband’s ship as it sailed along. This picture was done for Kenneth Roberts’ book Trending Into Maine, and I spotted it as a Wyeth first thing as we entered. I am a fan of both Roberts’ work and N.C. Wyeth’s, whose style is unmistakable. Roberts was the finest historical novelist the 20th Century produced, and N.C. Wyeth its greatest illustrator and artist. Putting Wyeth’s work into Roberts’ book was inspired. I have a copy of the first edition of Trending Into Maine and was tickled to see this rather small piece “in person” because the reproductions don’t really do justice to the brilliance and vividness of Wyeth’s images.

Another good exhibit was a bunch of ship models. I am “into” ships and ship models, and one of them was a huge model of RMS Queen Elizabeth that used to grace Cunard’s booking office. I may have seen it in situ in my pre- and teen years before the transatlantic passenger trade and its magnificent ships died: I certainly saw Queen Elizabeth many times when she was berthed on the West Side of Manhattan. Alas, like all the great liners she is now long gone: burned and sunk at her moorings in Hong Kong and broken up for scrap.

Queen Elizabeth in her prime: about 1966

The PEM’s is the largest and most detailed model of this great ship ever made. It weighs more than a ton and took special equipment to get it into the PEM.

There was also this very touching and unusual model of a ship as it was being dismantled for scrap. Most models show ships at their best, not at the end of their working life when they’re just pathetic piles of rusting metal in the breakers’ yard.

Then we went to see “The House of the Seven Gables”. This involved another game of Dodge-‘Em on Lowell Street. It’s funny how something that is essentially fictional can take on a life and pseudo-reality of its own. (We had previously encountered this phenomenon in Italy: in Verona tourists are shown “Juliet’s balcony,” purportedly the one from which the entirely fictitious Juliet bemoaned the equally fictitious Romeo’s status as a Montague in one of The Bard’s most famous scenes.) But the HOTSG really exists even if the story around it is fiction. It seems Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote the famous novel, used it as a setting because he had a cousin who lived there and he’d spent a lot of time in it. He was following the advice most authors get: “Write what you know.”

Then we went to see “The House of the Seven Gables”. This involved another game of Dodge-‘Em on Lowell Street. It’s funny how something that is essentially fictional can take on a life and pseudo-reality of its own. (We had previously encountered this phenomenon in Italy: in Verona tourists are shown “Juliet’s balcony,” purportedly the one from which the entirely fictitious Juliet bemoaned the equally fictitious Romeo’s status as a Montague in one of The Bard’s most famous scenes.) But the HOTSG really exists even if the story around it is fiction. It seems Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote the famous novel, used it as a setting because he had a cousin who lived there and he’d spent a lot of time in it. He was following the advice most authors get: “Write what you know.”

This cousin was a woman who inherited a fortune and remained unmarried because if she had taken a husband, all of her property would have become his. The protagonist of the novel is a woman who does the same thing. Many of the structural features of the House are worked into the book though nearly all the artifacts are not original to it. Later in its history (the 1920’s) the HOTSG was bought by a wealthy woman who used the income it generated to run a poor-kids’-benefit institution and today it’s a tourist trap. Next to it is “Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Birthplace,” which is to say the house in which he was born; but the house was somewhere else when that happened, and it was moved to its present site next to the HOTSG for the convenience of tourists.

Speaking of tourist traps, since we were in the area we simply had to make a short jaunt to Plymouth to see Plymouth Rock, the alleged landing site of the Pilgrims of 1620. We felt obliged as citizens to see this legendary place, hallowed ground even though by the time the Pilgrims arrived, the first English colony in the New World (Jamestown, Virginia) had been in operation for 13 years; the second settlement at Kilmarnock for 11, and the Spanish had been running St Augustine Florida for 99 years. Plymouth Rock is, well, a rock. Not even a very big rock, the one in our front garden is larger.

Speaking of tourist traps, since we were in the area we simply had to make a short jaunt to Plymouth to see Plymouth Rock, the alleged landing site of the Pilgrims of 1620. We felt obliged as citizens to see this legendary place, hallowed ground even though by the time the Pilgrims arrived, the first English colony in the New World (Jamestown, Virginia) had been in operation for 13 years; the second settlement at Kilmarnock for 11, and the Spanish had been running St Augustine Florida for 99 years. Plymouth Rock is, well, a rock. Not even a very big rock, the one in our front garden is larger.

The Rock is “housed” in a sort of open shrine, sitting at the bottom of a pit where it has been placed on a concrete plinth. I have my doubts about the story that the Pilgrims “landed” on Plymouth Rock anyway. It’s too far from the water for anyone to land a boat on it, let alone a sailing ship; and it appears not to be even close to sea level. Perhaps it’s been moved inland? In any event, the popular image of a man in a funny hat setting foot on a huge boulder is clearly wrong.

The best part of the trip as far as I was concerned was the few days we spent at our friends’ place on Cape Cod. The house is right on Cape Cod Bay, has a phenomenal view, and my friend Dave is a fanatical fisherman. Fishing is what I do when I can’t go hunting, so we took his two-man kayak into the Bay and tried our luck for stripers at high tide. That was no go, and to be brutally honest, a kayak, no matter how stable, isn’t my cup of tea. Especially not in even the mildest of ocean swells. If you head into the swell the bow (where I was sitting) goes up and down and often catches a wave. Even a small wave can be an issue: the damned thing sits so low in the water that a six-inch wave can dump water into the cockpit. If you’re broadside to the swell, it seems like it will tip over (though so far it never has). Plus you have to propel a kayak with a two-bladed oar; and though this looks easy it isn’t. It’s pretty strenuous, especially in any sort of wind.

Since we caught nothing we decided to go out the next day in a “head boat” based at Sesuit harbor. Albatross is an institution there. For a very modest fee they take you well out into the Bay to fish over steep drop-offs, wrecks, and other promising sites, supplying all the needed stuff as well: short stiff boat rods, bait, and workers who net the fish, ice it down, and filet it for you. This trip lasts a few hours and we did very well, bringing home several flounder and something called a “cunner,” which I’d never seen before. When I’m in North Carolina I occasionally catch a flounder and a good day there might produce two of them. I caught five that day. On my right were two girls about 8 or 9 years old who chattered and giggled incessantly, and were having the time of their lives. It was as much fun to watch them as it was to catch the fish. All in all a good run, and we brought home dinner.

Since we caught nothing we decided to go out the next day in a “head boat” based at Sesuit harbor. Albatross is an institution there. For a very modest fee they take you well out into the Bay to fish over steep drop-offs, wrecks, and other promising sites, supplying all the needed stuff as well: short stiff boat rods, bait, and workers who net the fish, ice it down, and filet it for you. This trip lasts a few hours and we did very well, bringing home several flounder and something called a “cunner,” which I’d never seen before. When I’m in North Carolina I occasionally catch a flounder and a good day there might produce two of them. I caught five that day. On my right were two girls about 8 or 9 years old who chattered and giggled incessantly, and were having the time of their lives. It was as much fun to watch them as it was to catch the fish. All in all a good run, and we brought home dinner.

Going out to the Cape we’d encountered unbelievably heavy traffic, especially on US 6, the “Mid Cape Highway”. Hours and hours to go a few miles. The return trip was much easier but then it was back into the maelstrom of Lowell Street and the usual Bostonian insanity. We had an early flight the next day so had reserved a hotel room in Revere for the night, as we’d had to return the rental car by 4:00 PM the day before. We dropped off the car and called the courtesy van from our hotel. The hotel was in a particularly seedy area and without a car we were condemned to eat in the hotel. Here’s a word of advice: don’t order “dinner” from the bar menu at the Hampton Inn in Revere unless you’re really into bad food.

The flight back to Richmond was uneventful (as all flights should be, of course) but when we arrived it was 102° and we had to wait over an hour for the courtesy van to come and fetch us so we could retrieve our car. After the cool breezes of Maine and the Cape it was a real shock to be back in The Sunbelt.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |