Make Mine A Little One: In Praise Of Little Guns

Make Mine A Little One: In Praise Of Little Guns  Make Mine A Little One: In Praise Of Little Guns

Make Mine A Little One: In Praise Of Little Guns

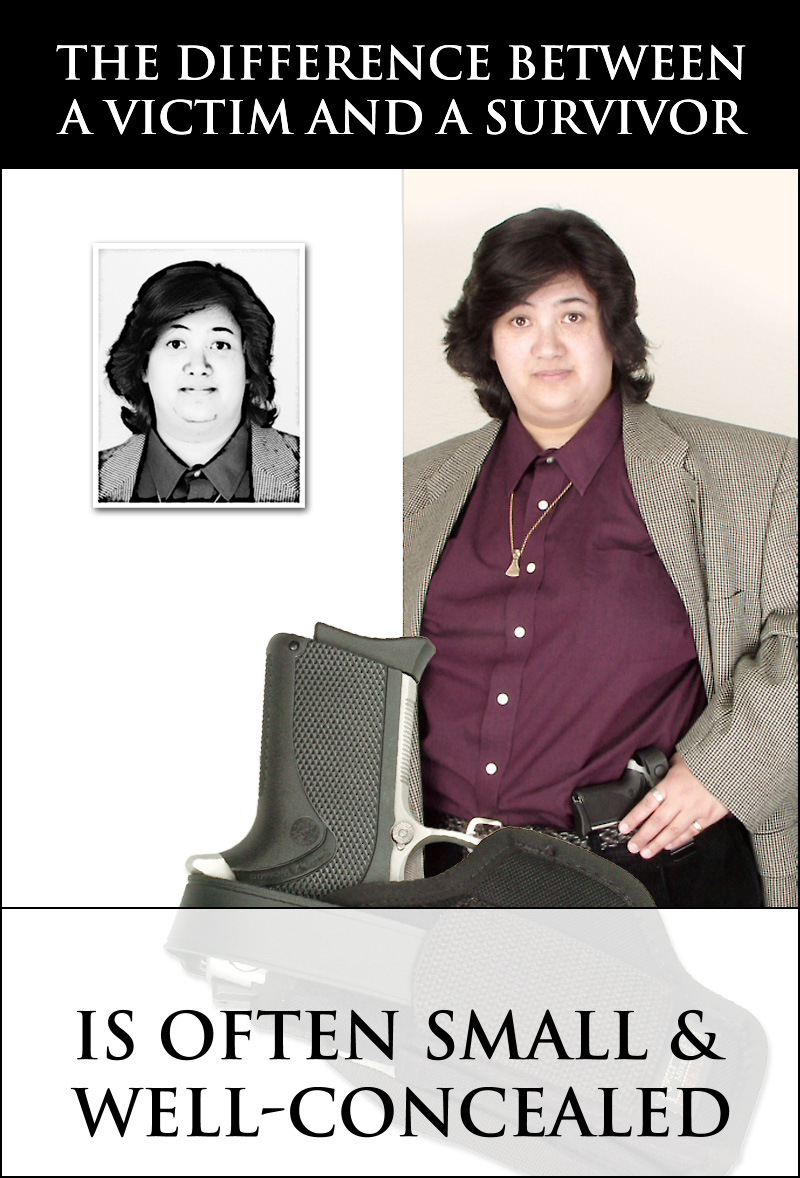

With the welcome expansion of "shall issue" and "constitutional carry" laws in so many American states the number of citizens lawfully carrying concealed weapons has greatly increased. This is by and large a good thing: now in most jurisdictions (with the exception of places like New York City and some other vehemently anti-gun localities) a Bad Guy cannot be certain a potential victim isn't armed unless, of course, he strikes in a so-called "gun-free zone" as so many of them have learned to do.

From time to time I get asked about what kind of gun I recommend for someone to buy and specifically to carry. There are a number of considerations to be borne in mind but the title above suggests one answer I often give.

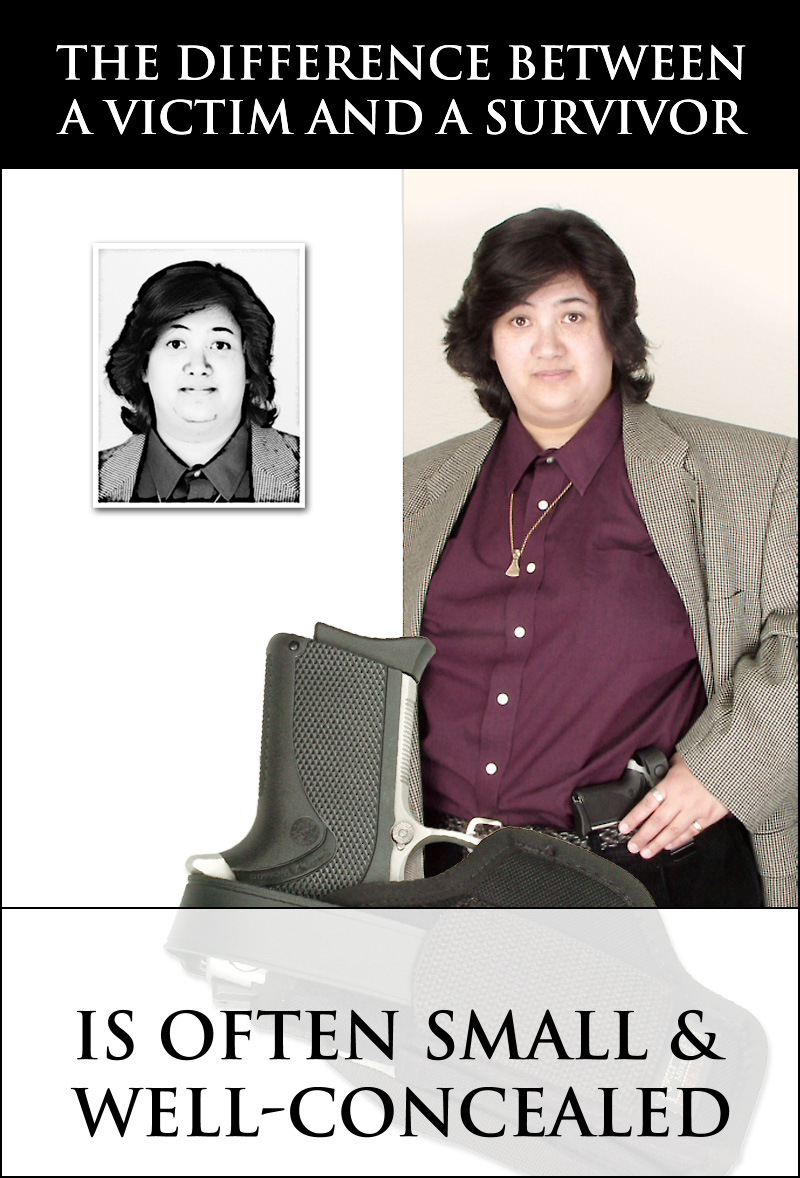

The quasi-official slogan of modern handgunners and the magazines they read seems to be, "Bigger Is Better! " It's a rare issue of a gun magazine that doesn't carry an article on the latest effort to push the envelope of handgun power. Breathless reportage of yet another Superblaster wildcat or a white-hot load for an existing caliber is the rule. Velocity and energy figures that dwarf "mild" factory loads (even in Magnum calibers) are the order of the day, as are outsized sights sometimes larger than the pistols on which they’re intended to be placed. In a way you can't blame the gun writers: their job is to sell guns—new guns, not used ones—so they have to satisfy their editors and advertisers.

But it’s hard to justify—sometimes it’s hard to understand—some of the excesses the Monster Handgun Craze has produced. My vote for Craziest Handgun Idea is an add-on unit to turn a Colt M1911-A1 into a bolt-action single-shot firing a bottle-necked proprietary 7mm cartridge. The proud creator of this monstrosity advocated topping it off with “...a suitable electro-optical sight.” Thus he turned a classic pistol—one credited with legendary performance for more than a century—into a cumbersome, butt-ugly hybrid requiring a sling, moreover one whose ballistics are inferior to a .30-30 carbine. Then there are the S&W "X" frame revolvers, some of which are equipped with a sling and at least one of which comes with...are your ready?...a bipod.

Are these really handguns? Generically, perhaps, but not in any meaningful sense. Such things have no relation to the Real World. They’re the products of writers looking for story ideas, or Gearheads in the wholly artificial environment of competition shooting. Tweaking, tuning, twisting, and transforming practical handguns into single-purpose machines may have some experimental (and certainly economic) value, but those guns bear the same relationship to the vast majority of handguns that a Formula One race car does to the family sedan. The two are specialized for entirely different purposes. Trying to sucker the public into buying this stuff is hard to defend.

The historical development of the handgun followed three parallel tracks: military applications, personal defense use, and hunting. The concept of handguns as serious hunting weapons is relatively new (dating from about 1960). It’s a lot of the driving force behind the urge to hot-rod pistols such as the S&W X-frames noted above. But it need not be considered here, because most handguns are bought as personal defensive weapons. The power and fury of a .454 Casull or the .500 S&W is irrelevant in that context. Defensive use of handguns takes place at short ranges and against man-sized animals in a house or on dark city streets, not Alaskan grizzly bears at 50 yards.

The “hand” gun per se is as old as firearms technology. Nobody really knows when the "hand gonne" was invented, but the Chinese knew about gunpowder in the 13th Century; it's a pretty safe bet that someone figured out how to use it in a weapon. Certainly images of cannons exist from not much later, but I'm not concerned with cannons. The earliest known European illustration of a firearm dates from the mid-14th Century, not long after the technology of gunpowder reached the West via trade routes. It shows a vase-shaped cannon. No doubt its working models and prototypes were small enough to be held by one man. While the many references to "hand gonnes" in early inventories of arms are usually taken to mean shoulder-fired pieces, many of them were small enough to be carried and fired with one hand. In the reign of King Henry VIIIth “hand gonnes” with barrels less than a certain length were not permitted as they were too easily concealed on the person. (Does this sound familiar?)

The “hand” gun per se is as old as firearms technology. Nobody really knows when the "hand gonne" was invented, but the Chinese knew about gunpowder in the 13th Century; it's a pretty safe bet that someone figured out how to use it in a weapon. Certainly images of cannons exist from not much later, but I'm not concerned with cannons. The earliest known European illustration of a firearm dates from the mid-14th Century, not long after the technology of gunpowder reached the West via trade routes. It shows a vase-shaped cannon. No doubt its working models and prototypes were small enough to be held by one man. While the many references to "hand gonnes" in early inventories of arms are usually taken to mean shoulder-fired pieces, many of them were small enough to be carried and fired with one hand. In the reign of King Henry VIIIth “hand gonnes” with barrels less than a certain length were not permitted as they were too easily concealed on the person. (Does this sound familiar?)

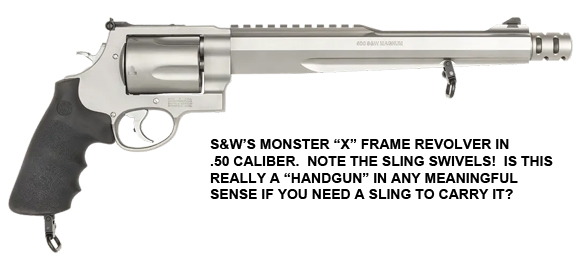

No later than the early 16th Century the technology of gunpowder weapons had evolved to produce true “handguns” i.e., weapons designed and intended to be fired with one hand were available to be used in warfare, and presumably in self-defense. The practicality of a small firearm was glaringly obvious to the cavalryman. The need for weapons light and compact enough to handle on horseback—without losing control of the horse—drove the evolution of the handgun as we know it well into the 20th Century. So much so that the modern fighting pistol is the logical consequence of firearm design concepts rooted in the 15th and 16th Centuries. The matchlock and wheel-lock handguns of the 16th Century were large and unwieldy by our standards, yet small enough to give a cavalryman a way to unseat an opponent (or to disable his horse) in the melee of a cavalry battle. The Model 1911 Colt autoloader used by US forces for more than a century is the direct, lineal descendant of the "hand gonne" of the 16th Century cavalryman. The value of handguns to naval boarding parties engaged in arm's-length scuffles for control of a ship is also obvious.

No later than the early 16th Century the technology of gunpowder weapons had evolved to produce true “handguns” i.e., weapons designed and intended to be fired with one hand were available to be used in warfare, and presumably in self-defense. The practicality of a small firearm was glaringly obvious to the cavalryman. The need for weapons light and compact enough to handle on horseback—without losing control of the horse—drove the evolution of the handgun as we know it well into the 20th Century. So much so that the modern fighting pistol is the logical consequence of firearm design concepts rooted in the 15th and 16th Centuries. The matchlock and wheel-lock handguns of the 16th Century were large and unwieldy by our standards, yet small enough to give a cavalryman a way to unseat an opponent (or to disable his horse) in the melee of a cavalry battle. The Model 1911 Colt autoloader used by US forces for more than a century is the direct, lineal descendant of the "hand gonne" of the 16th Century cavalryman. The value of handguns to naval boarding parties engaged in arm's-length scuffles for control of a ship is also obvious.

Admiral Horatio Nelson (in the right foreground, in a white uniform) used a "sea service" flintlock pistol (visible in his left hand) similar to the one shown here, at the battle of Cape Saint Vincent in 1797. As technology progressed percussion ignition succeeded flintlocks, but handguns were standard equipment in the days of "wooden ships and iron men" when boarding an enemy vessel was a normal battle tactic: during the American Civil War the US Navy issued 6-shot .36 caliber Colt revolvers.

The US Navy still issues handguns to its officers and boarding parties. The 9mm caliber Beretta M9 is standard issue but some specialized units still use the good old tried-and-true .45 ACP.

Military use of handguns quite naturally carried over into civilian life, but the transition imposed a significant additional requirement: concealability. Soldiers can carry arms openly, but civilians usually don’t even where this is permissible. Common sense, discretion, and the need to avoid even the impression of aggressiveness mandate that the hardware be kept out of sight. This fundamental distinction has persisted to modern times and it’s been the principal force in the evolution of recent handgun designs. Therefore I will discuss below concealed weapons and what I believe is advisable should someone decide to carry one.

Consider this: a civilian’s concealed personal defense handgun must be, in order of importance, 1) utterly reliable; 2) small enough to be effectively hidden; 3) as light as possible; and 4) reasonably powerful. Power ranks a long way last because only rarely will the gun ever be drawn let alone used. A civilian’s personal protection handgun ideally should be with him all the time, and the more comfortable it is to tote around the more likely he’ll have it when it’s needed. I’ve carried a gun off and on for 60 years. I’ve had to draw it only once; but never have I had to fire a shot in anger. Yes, there have been times when I carried a .45, one that weighs two-and-a-half pounds loaded. At the end of one of those days, taking it off my belt was my definition of “relief.”

Consider this: a civilian’s concealed personal defense handgun must be, in order of importance, 1) utterly reliable; 2) small enough to be effectively hidden; 3) as light as possible; and 4) reasonably powerful. Power ranks a long way last because only rarely will the gun ever be drawn let alone used. A civilian’s personal protection handgun ideally should be with him all the time, and the more comfortable it is to tote around the more likely he’ll have it when it’s needed. I’ve carried a gun off and on for 60 years. I’ve had to draw it only once; but never have I had to fire a shot in anger. Yes, there have been times when I carried a .45, one that weighs two-and-a-half pounds loaded. At the end of one of those days, taking it off my belt was my definition of “relief.”

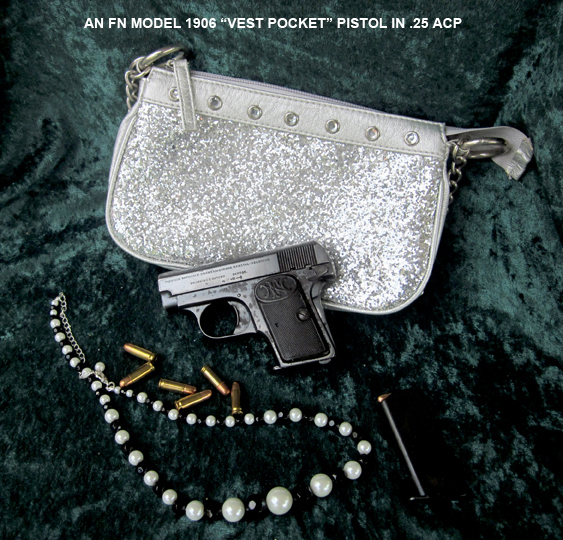

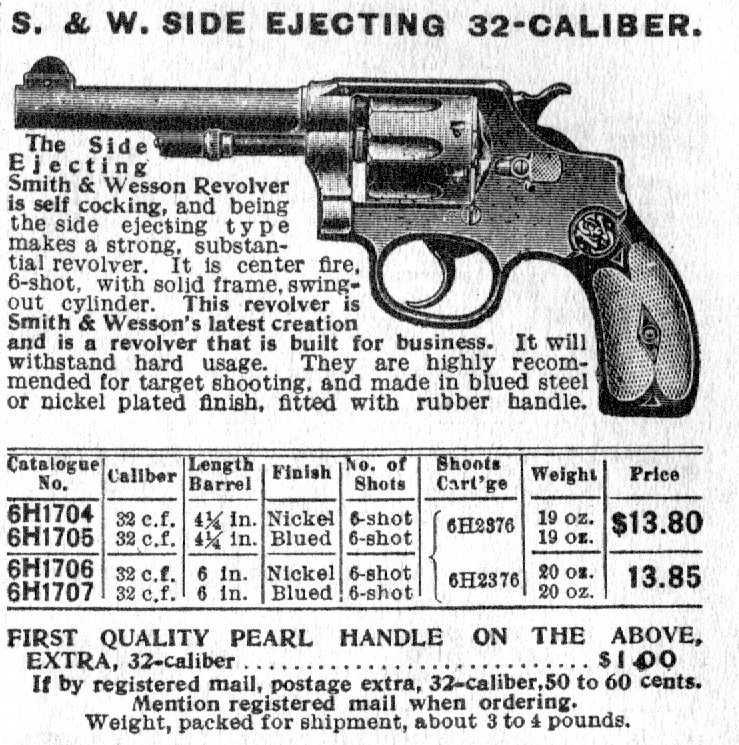

It should be obvious that better concealability can only be paid for by accepting lower levels of power and size. This is a trade-off taken for granted until fairly recent times. The typical personal protection handgun in the pre-World War Two period was chambered for what gun writers now deride as “inadequate” calibers. Small .32 and .38 caliber revolvers, and .25 and .32 caliber pistols, sold in uncountable millions in America and Europe precisely because they were so suitable for day-to-day carry. Most civilians emphatically do not need raw power in a handgun, and are better off without it, though you would hardly know this from reading magazine articles.

It should be obvious that better concealability can only be paid for by accepting lower levels of power and size. This is a trade-off taken for granted until fairly recent times. The typical personal protection handgun in the pre-World War Two period was chambered for what gun writers now deride as “inadequate” calibers. Small .32 and .38 caliber revolvers, and .25 and .32 caliber pistols, sold in uncountable millions in America and Europe precisely because they were so suitable for day-to-day carry. Most civilians emphatically do not need raw power in a handgun, and are better off without it, though you would hardly know this from reading magazine articles.

A private citizen is always counseled (and in most jurisdictions required by law) to avoid confrontation and to be as reluctant to employ deadly force as he can within the limits of saving himself from lethal harm. This mandate is a counterweight to the concept that “power is paramount.” Of necessity it's best served by small guns.

What might be termed “Close Encounters of the Extremely Serious Kind” are usually just that: close. Almost all incidents of civilian self-defense (if they involve any shooting at all, which most don’t) take place at ranges well under 30 feet (and usually under 20). If a man intent on harming you is within that distance, you may have few if any alternatives to deadly force, assuming you have complied with the obligation to avoid trouble. If he’s much farther away you’re going to have a hard time making a credible argument that it was necessary to kill him. Twenty feet is close enough so that even a small gun can be effectively employed by someone who is trained properly. “Self-defense” in a civilian legal context never calls for 50- or even 25-yard shots, so the buck-and-roar of a big handgun is not needed.

Another point to consider: the commercial ammunition available for civilian use is often more effective than military issue, all other things being equal. "Full-metal-jacket" bullets are used in military weapons. The stopping power of “hardball” is based on bullet size and velocity but a civilian can choose ammunition whose performance is enhanced by better bullet designs. Effective performance in a defensive context is much discussed in the shooting press but the hype is always towards the bigger-is-better argument. Here’s something they don’t tell you: very few handguns (especially if they’re small enough to carry under a jacket) can move a bullet much faster than 900 feet per second (FPS). The few that do exceed that velocity must have larger size and weight, just to make them controllable at all. For example, in a 2” barreled .357 Magnum, full-power loads will generate a fireball easily visible in broad daylight. Needless to say such a gun is a cast-iron beast in recoil*. The “solution” the magazines offer for a .357 Magnum you can't handle is.…shoot .38 Specials in it! This will certainly make the gun easier to shoot, but doesn’t do anything about the size and weight. The .38 Special was for many years the standard police handgun caliber. With modern ammunition it will still do the job for which it was intended, though the writers will try to convince you otherwise.

Another point to consider: the commercial ammunition available for civilian use is often more effective than military issue, all other things being equal. "Full-metal-jacket" bullets are used in military weapons. The stopping power of “hardball” is based on bullet size and velocity but a civilian can choose ammunition whose performance is enhanced by better bullet designs. Effective performance in a defensive context is much discussed in the shooting press but the hype is always towards the bigger-is-better argument. Here’s something they don’t tell you: very few handguns (especially if they’re small enough to carry under a jacket) can move a bullet much faster than 900 feet per second (FPS). The few that do exceed that velocity must have larger size and weight, just to make them controllable at all. For example, in a 2” barreled .357 Magnum, full-power loads will generate a fireball easily visible in broad daylight. Needless to say such a gun is a cast-iron beast in recoil*. The “solution” the magazines offer for a .357 Magnum you can't handle is.…shoot .38 Specials in it! This will certainly make the gun easier to shoot, but doesn’t do anything about the size and weight. The .38 Special was for many years the standard police handgun caliber. With modern ammunition it will still do the job for which it was intended, though the writers will try to convince you otherwise.

That 900 FPS is pretty much pushing the envelope: most pistols for concealed carry have fairly short barrels, so let's peg the velocity lower, say 750 FPS. A .38 Special with a 158 grain bullet at that speed will generate 120 Foot-pounds (F-P) of muzzle energy. That's with "standard" round-nosed lead bullet ammunition like the cops used to use. Nowadays better bullets are available, but let's take it as a yardstick.

From this image it should be clear that as the caliber gets bigger so must the gun it's fired from.

At the bottom of the scale is the .25 ACP (I'm deliberately ignoring the .22 Long Rifle or .22 Magnum here) shooting a 50-grain bullet. It's often derided as a "mouse gun" but it still has 63 F-P of energy. The somewhat larger "pocket gun" rounds, the .32 ACP and .380 ACP are a step or two up: 89 F-P and 120 F-P respectively. The mighty .44 Special outclasses all these at 314 F-P; while it's a great self-defense round in general the guns to shoot it are large enough to make easy concealment harder. No one in his senses wants to get shot with any of these, even the peashooter .25 ACP. Of course in a tight spot you might very well be dealing with someone who is not in his right mind.

Inevitably I get asked, "What about a 9mm?" "What about a .357 Magnum?" or "What about a .40?" Any of these are fine defensive calibers but they come in guns that are larger than I like. Kel-Tec used to make the "PF9" in 9mm but it is discontinued. It was about as small as a 9mm can be and was reportedly vicious in recoil. Similarly their slightly-larger P11, also in 9mm, is out of production. Kel-Tec used to make a variant of the P11 in .40 S&W: I don't even want to think about shooting one of those.

Also inevitably I get asked, "What about a .22?" There are two possibilities here. One is the tried-and-true .22 Long Rifle, a caliber ideal for small game but not for self defense. Oh, sure, it can be used and doubtless has been many, many times, to defend oneself. But the bullets are even smaller than the .25 ACP (only 40 grains) with a power level at 750 FPS of 50 FP. The other option is the .22 Magnum. This is, to my knowledge, only available in an autoloader far too large to conceal easily. It really is only a round for use in rifles. At 750 FPS its 50-grain bullet has exactly the same ballistics as the .25 ACP. Either will work, if the shooter is cool, calm, and able to place shots perfectly, but a) that's true of any handgun; b) not a description of the average civilian under lethal threat. I wouldn't recommend either. So much for the rimfire calibers.

Now, that word “Magnum” casts a spell over the average shooter. Americans believe that velocity is the best measure of bullet performance; this is true up to a point. But most people don’t understand that you're far better off using heavy bullets at moderate velocities than light ones at super speeds. Look at the numbers above. Actually paper energies mean little: what matters is momentum, the tendency of a bullet to continue to move in a straight line after impacting a target. Heavier bullets do that better than light ones which can be deflected by bones or even clothing. Furthermore if you're able to control the gun better, you can place your shots more effectively. Muzzle blast is meaningless. It may look impressive in photos but it contributes nothing whatever to the performance of the gun in a 20-foot lethal fight. Worse, it may temporarily blind the shooter or even cause a flinch during practice sessions. No one is well served by a gun that he’s afraid to fire.

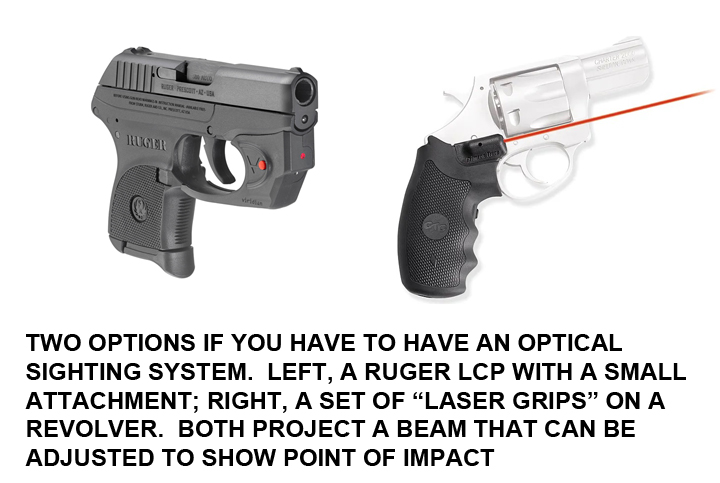

Another thing most people simply don’t need on a concealed defensive handgun—this is heresy, but it’s still true—is adjustable sights. Shot placement is the most important factor in effective use of the handgun, but in a 20-foot encounter where the target is a man’s chest, it isn’t hard to achieve a level of proficiency that will deliver the goods if the gun is one the shooter can control. With minimal practice almost anyone can keep four out of five shots inside a 20 x 20-cm square at 20 feet or less (especially with an autoloader). Adjustable sights add nothing but bulk and the possibility of snagging themselves on clothing. Low, wide-notch fixed sights, perhaps enhanced by white paint for easy visibility, are much preferable. A rear sight that can be drifted in a dovetail is the ideal compromise between adjustment and minimal bulk. Elevation isn't a concern at 20 feet or less.

Still less does anyone need an "optical" sight on a defensive handgun. These are no doubt very precise but in a short-range shootout they provide few if any advantages to offset their drawbacks. Optical sights, of necessity, add bulk (if not weight) and make concealment much more difficult. We're sometimes advised to use a revolver with a "spurless" hammer to make it less prone to catch on clothing. How come, I wonder, we  are never so advised about a sight that sticks up half to three-quarters of an inch above the frame of the gun, requires a modified holster, and presents a significant likelihood of snagging? On a gun to be kept in the house such a sight might make sense, especially in a darkened room, but for concealed carry on the street?

are never so advised about a sight that sticks up half to three-quarters of an inch above the frame of the gun, requires a modified holster, and presents a significant likelihood of snagging? On a gun to be kept in the house such a sight might make sense, especially in a darkened room, but for concealed carry on the street?

There are some "add-on" items for small pistols that add only minimal bulk and weight. These usually take the form of grips with a built-in laser or a piece that attaches to the trigger guard with that capacity. I think they're a frill but perhaps a useful one. Once the gun is sighted in you put the projected dot on the target and fire.

There are legal considerations to be kept in mind. Kill or even seriously injure a man in self-defense and your motives will be examined very carefully by the authorities. Do it with a tricked-out gun equipped with optical sights on a Picatinny rail, using any ammunition labeled "Magnum" and you might well have to do some 'splainin' to a judge. Shoot someone at 25 yards and this is a certainty.

In theory one is innocent until proven guilty but you may well find yourself in a courtroom defending your actions. Even if it's not a criminal trial you may well face a civil proceeding for "wrongful death" brought by the relatives of the person you shot. A zealous prosecutor or plaintiff's attorney, especially one who is anti-gun, may paint you as a bloodthirsty killer "looking for a victim" and equipped with "an especially deadly weapon." Don't think this doesn't happen: the case of Daniel Penny in New York City is an example of what can occur.

A minor consideration—this is advice I paid a lawyer for and I pass it along for free—is not to use a gun that has any sort of sentimental value. Why? Because if you use it—and maybe if you don't but the police are called—you may not get it back. Even in a righteous shooting, even if you aren't charged with anything, it will almost certainly be impounded as "evidence" and if you get it back at all, it will have been defaced with evidence control markings as it made its way through the police and court hands. Get a good, solid, reliable gun you won't mind losing.

Above all, never, ever, ever, used reloaded ammunition in a self-defense pistol. Use factory ammunition, preferably of the same style used by your local police force. If you use reloads—even if they aren't your own but some you bought—a prosecuting attorney will probably try to paint you as a cold-blooded killer. If you use the same stuff your police uses he really can't do that. If your local cops use hollow points, find out what brand and buy it in the caliber you choose, but never, and I mean never use any sort of reloads.

The standard answer we to give to trainees in our Personal Protection courses who ask "What should I buy?" is to get "...the gun you shoot most effectively..." modifying that advice if the gun is to be carried concealed rather than kept in the home. In keeping with the idea that a defensive handgun should be as unobtrusive as possible, should be comfortable to carry, should provide a serious level of protection in a dire situation, and should be defensible in court, I always recommend a small autoloading pistol. Why an autoloader? Because these are almost always thinner, lighter, and more compact than revolvers of comparable power, thus more easily concealed. Even a fairly good-sized autoloader can be hidden under a jacket because it's flat. But a small gun can be carried in a pocket (using an appropriate holster) even when wearing casual clothing. This is an advantage not to be sneezed at. A gun in a pocket is invisible. A gun underneath what the NRA (in its ineffable taste for euphemisms) calls a "concealment garment" such as a jacket, may or may not be if the jacket flips open. If that happens and someone screams "GUN!" your life may become very awkward. Ditto if it falls out of a holster onto the floor during a party. It may be perfectly legal but you likely won't get invited back to dinner.

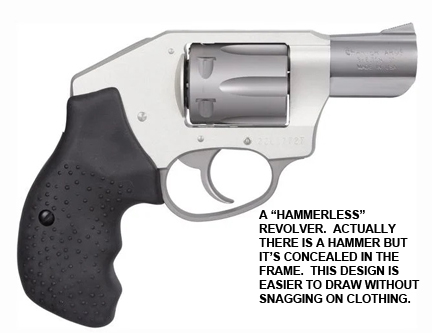

On the issue of revolvers vs. autoloaders, I certainly think a small revolver is not a bad choice if the user is confident and capable with it. A small revolver is fairly easy to conceal. Charter Arms makes the "Undercoverette" in .32 Magnum, a good caliber but it can be hard to find. But the Undercoverette is the same size as Charter's .38 caliber revolvers like the "Off Duty." Though it has the advantage of one extra shot compared to the .38's there is no size difference. As a matter of fact, both the Undercoverette and the various Charter .38's are all the same size and will fit a holster for a "J" frame S&W if you opt for using a holster.

One other point about revolvers: the best option is to get one with a concealed hammer, or at the very least a "spurless" hammer. These will greatly reduce the chances of the gun being snagged when drawing it. It will mean learning to shoot double-action-only but up close and personal there's not much time to cock a hammer and aim deliberately anyway.

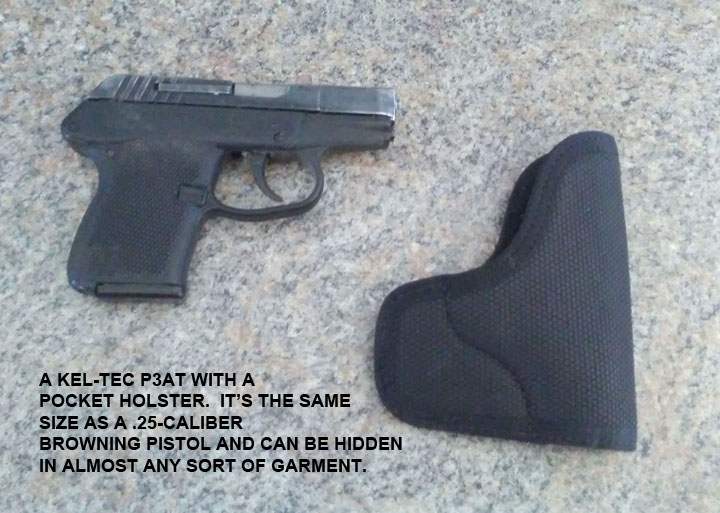

As mentioned, in the past the .25 ACP and .32 ACP were immensely popular but today there are better options. For many years I carried a .25, then stepped up to a .32, but on today's market there are pistols in .380 ACP caliber that are as lightweight, compact, and concealable as any .25 or .32: Kel-Tec's "P3AT," Ruger's copy of it, the "LCP," and S&W's "Bodyguard." (Alas the P3AT has been discontinued in the face of stiff competition from Ruger and S&W but its little brother the P-32 is still in the lineup. The P3AT can be still be found used pretty readily.) All three of these little guns use the .380 ACP. In my opinion it's as good a compromise as can be found between weight, size, power, and concealability. The .380 has in fact long been issued as a police caliber in some European countries.

Full disclosure: my own "every day carry" is a Kel-Tec P3AT, one I bought in 2004. Prior to that I had a P-32 (which is exactly the same size) and before that a pretty little FN M1906 "Vest Pocket" in .25 ACP. I have never felt under-gunned even with the .25. My Kel-Tec in .380 fits into the holster for that little FN. I can, and have, hidden it in a bathing suit pocket. For sheer horsepower-to-weight ratio it's unmatched.

Luckily I have never been put to the test of using a pistol in self-defense (I came close once many years ago but never fired a shot) but if I ever am, it will be the .380 that's in my pocket, not a .45 I left at home because it's too heavy. I mentioned carrying a .45 once, and my relief at getting shed of it above: it was in Richmond, Virginia, a city known for pretty high levels of violent crime. I am lucky enough to live in a pretty low-crime area (of course, there's no such thing as an absolutely "zero-crime area") so my .380 will, I think, be adequate for anything I might encounter. If I were to somehow find myself living in Richmond I might re-think things and carry my .44.

| OPENING PAGE|

|SEASON LOGS |

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |